What if the game was intentional? Is boring? This feels like the premise of Harold’s Halibut , which is kind of brilliant at first. You play here as the eponymous Janitor, a kind of lab assistant, slash administrator, and general purpose dog on Fedora. Fedora, a colony spacecraft that crashed from Earth in the late 1970s or early 1980s, has now been trapped deep in the oceans on a mostly liquid planet for about 60 years, becoming a self-sufficient ’s commune, only partially longing to go home.

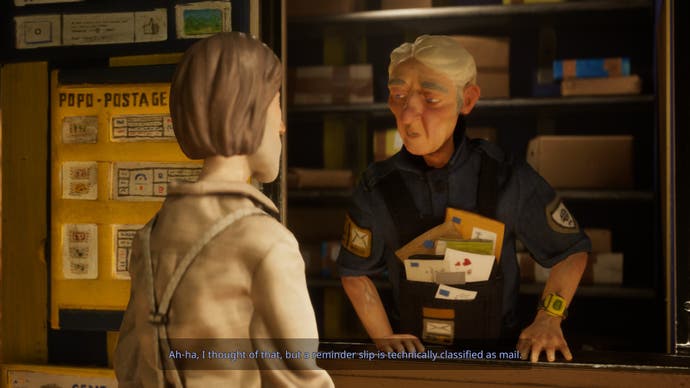

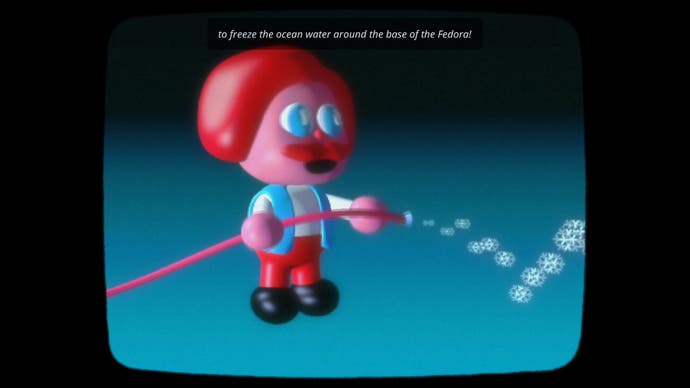

It’s a wonderful setup that allows debut developer Slow Bros to make some of its best work. Fedora is a remarkable piece of human artefact, and the game is composed of hand-crafted, intricately worn and weathered models and sets that have been digitally used for animation. Combined with period selections, you get this Aardman-esque visuals and a deeply retro British humor centered around bureaucratic post office procedures and the value of different forms of work. For example, the ship itself – green, underwater, slightly industrial, like a miniature village built inside a level – has been gobbled up by the humble town company All Water, surrounded by small CRT televisions that intermittently Buzzing. with corporate TV commercials and announcements.

In these—and similar opportunities for meandering, choppy audio-visual feeds or shaky old-school laboratory computing moments—Harold Halibut is probably at his best. The animations, decorations, and nifty little buttons make it completely mesmerizing even in very elementary puzzles. When humor emerges, it takes aim at a niche but ever-present part of the British collective psyche, namely the selfish entrepreneurial mentality of a very specific kind of close-minded, curtain-pushing middle-class 80s generation. Unfortunately, moments like this are rare, and the better parts of the rest of the game are undermined by the relentless, brutal, infinitely slow pace of things.

Take the early discovery that Fedora is facing an energy crisis as an example. Prepare to be the perfect inciting incident, after which your first few missions instead revert to your usual routine: jog to different areas of the ship, delivering a message from one professor to another, or, if you’re lucky, , may bring back an object, etc. This is punctuated by some meandering conversations with other Fedorans about their day-to-day problems, as well as some optional side quests, before returning to the small cot in the lab basement to start the day again.

At first, the conversations are funny: you learn that Chris Tenenbaum is a passionate but sensitive teacher obsessed with Turkish TV melodrama. A shop owner keeps making grand moves to win back the love of his scientist wife, when her main problem is actually that she just needs a little space to do her job. An affable elderly postman named Buddy enjoys jogging through the Arcade District, a small row of shops and restaurants that exist beneath an alien sea of green like a slice of life frozen in time, complete with delightful Sleepy elevator music.

While this sleepy pace makes room for some truly touching moments—especially later involving Buddy’s mission and some undelivered letters—it’s also Harold Halibut’s biggest problem. part. Slowly, as you travel back and forth between the “pipeline” connections from one region to another, you’ll discover some minor tensions among the citizens of Fedora. But despite the urgency of your mission to regain your strength and escape back to Earth, and despite Harold’s heartbreak and sometimes overwhelming desire for more, the change of pace never comes.

On the contrary: more discoveries, more mysterious seeds or more narrative threads to unravel, which delays the story’s conclusion but doesn’t really enhance it (there’s a lot of superfluous plot here that takes too much time to resolve , about a dozen hours or so, for something as complex as a chicken run) and a more lazy trot back and forth in the same environment.

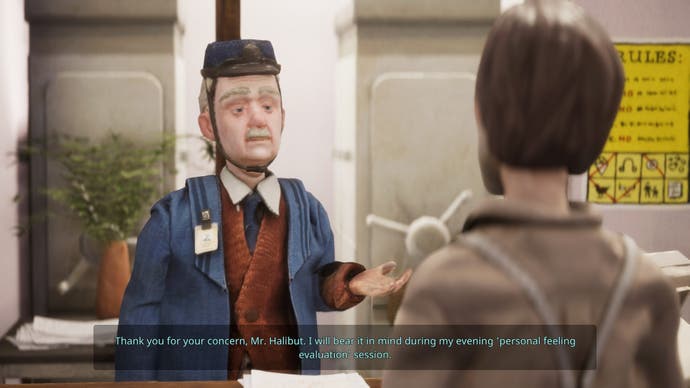

Retrieving tasks again and again will gradually tire you out. One time, I was assigned to deliver a message to someone — and by the way, remember, everyone can text each other here — it was literally: “Hello, how can I help? ” Just getting there and having the person tell me they didn’t need any help, or wanted to chat.Then when I went back to the source I was told them Anyway, it doesn’t matter at all. Even this happened not once, but several times. (One character in particular was known for never being willing to help, but on several occasions I was sent to ask politely and was turned down, which surprisingly didn’t matter as other issues arose , solved this problem)problem).

Each small journey takes a few minutes: coming out of the laboratory, along the corridor to the subway, through the subway to the station, where you change to a different subway line to your destination, along another corridor, through another long , chat, and then all the way back.It happens so often that your time is wasted so aggressively and unceremoniously that it gives the impression that this must is intentional, it’s a way to put you into Harold’s miserable situation and pass some of his existential crisis onto the player. But even if it were seen as an intentional installation, it wouldn’t get off the ground.

Part of this is due to the characters themselves, many of whom are colleagues and friends, but also almost uniformly condescending, selfless and even cruel.I doubt this no on purpose. Harold is often overlooked and underused, which is certainly an intentional theme, but the writing here is chaotic. Harold was sullen, untalented, and a bit dull, often inserting into conversations ideas that everyone had already thought of but had dismissed. Meanwhile, the other characters’ lines are structured in their own way. Can

Like most of Harold Halibut’s stories, this doesn’t progress at all during the game. Up until the final act, I still found myself being berated as a “fool” and blamed for things completely beyond my control, as Harold continued to huff and puff, and even in the revelatory third act experience, he was nothing more than A component. Combined with the large number of jokes that don’t quite land, and some truly interminable dialogue, the writing becomes quite a drag. There’s an intermittent bug in Harold’s Halibut where when you jump ahead it will unexpectedly advance the entire conversation rather than just the current line, making everyone in the room speak at the same time – but sometimes I really So glad it came out. Skim through conversations quickly and rarely miss anything important.

Ultimately, the effect is one of gradual erosion, with repetition wearing away the impact of certain small elements of scenes, dialogue, and even visual detail. I loved Fedora’s floors, its mechanical quirks, the hand-drawn posters on its walls, and its angular medieval utopian social zones, but I fell less in love with them the hundredth time I walked past them. The same goes for the little London Underground-style announcements when getting on and off the tube: cute at first, but I fell less in love with them once I had to make several tube journeys back and forth in a matter of minutes.

Even the game’s big, climactic visual moments last too long. Encounters with alien species (not a spoiler, don’t worry), and a trip to their special cave, complete with strange musical installations and food vendors, were like a particularly hippy exhibit on South Shore that took too long and lacked Too much purpose, failing to offer much in the conversation beyond a faint philosophical shrug. That, and some of the late-game sequences are being shot somewhere around The Beatles meets Pink Floyd, but fall into the trap of a lot of the potentially enlightening prog rock can do, again here I lingered on one point for too long.

This is a huge shame and a waste. Parts of Harold’s Halibut are striking, and the world itself is a true achievement of touch and human craftsmanship. Its story asks the right questions — the big questions, about why we are here, who we meet, and what we should do with it all. The idea, at least in theory, is a bit genius. Harold Halibut is a true anti-hero and actually a passenger in the story played out by real experts.

What happens when a story not only doesn’t get you picked, but doesn’t give you any preferential treatment at all?You have no qualifications at all, just being in the right place and the right time, and a real expert No Naturally, they use this as an excuse to drag you to their side and make you the de facto protagonist from now on? What happens if fetching is your job and you crave more stuff, but in reality, fetching stuff is all you can really do? What if, in trying to bog down the player directly, you deliberately patronize them, waste hours of their time, and make them really bored?

When I say this is awesome, I really mean it. If this was indeed my intention, as I think it was, then I’m glad to have played a game that attempted this – as Harold Halibut’s boss often lamented, such scientific experiments are okay no matter the outcome very interesting. In this case, some better execution would certainly have helped, but despite there being moments of genuine beauty, invention, and craftsmanship, some heartfelt philosophy, and genuine warmth, the premise might have been a bit off from the get-go. defect.

Slow Bros provided a copy of Harold Halibut for review.