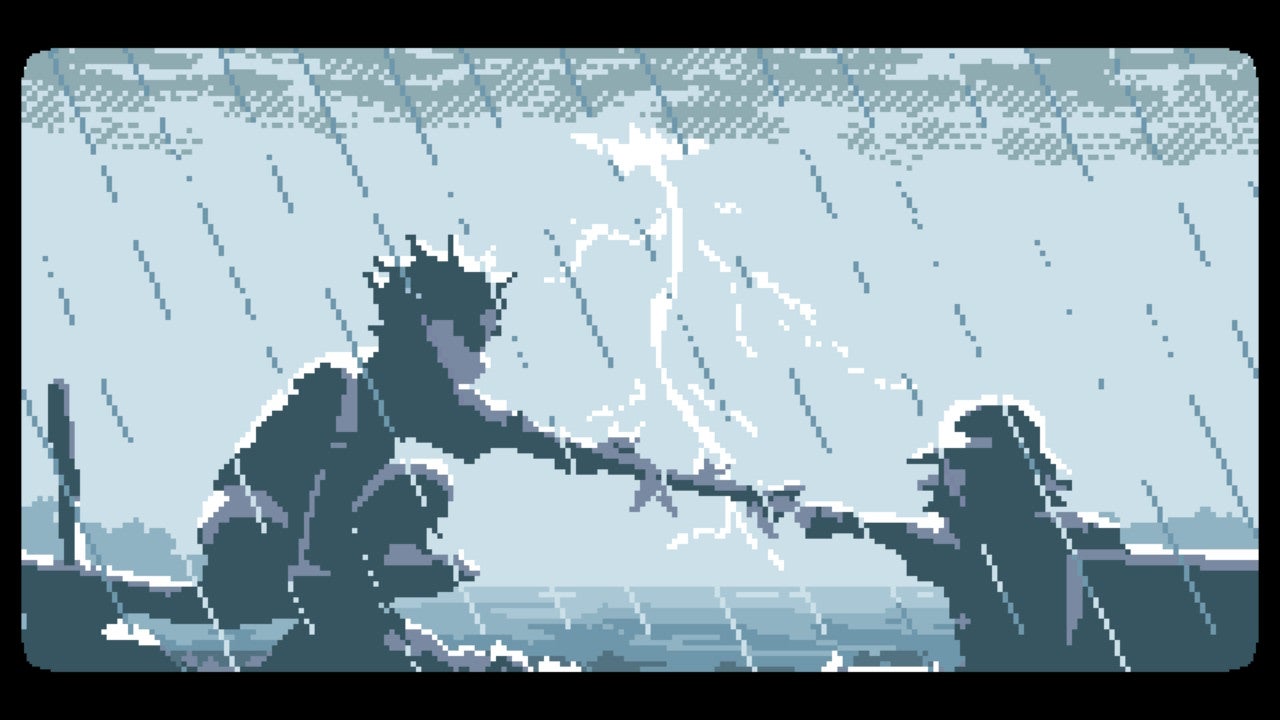

Many indie games deal with anxiety and depression, but few include such raw and intense pain as A Space for the Unbound. Following a group of teenagers through the difficulties of school life and beyond – beyond space and time – is awkward at times, too eager in some areas, dawdling too long in others, and often figuring out where it’s going. Along with teenage earnestness, charisma and, more importantly, sincerity, raw sincerity. A Space for the Unbound feels a lot, feels tough, and turns out to be intoxicating.

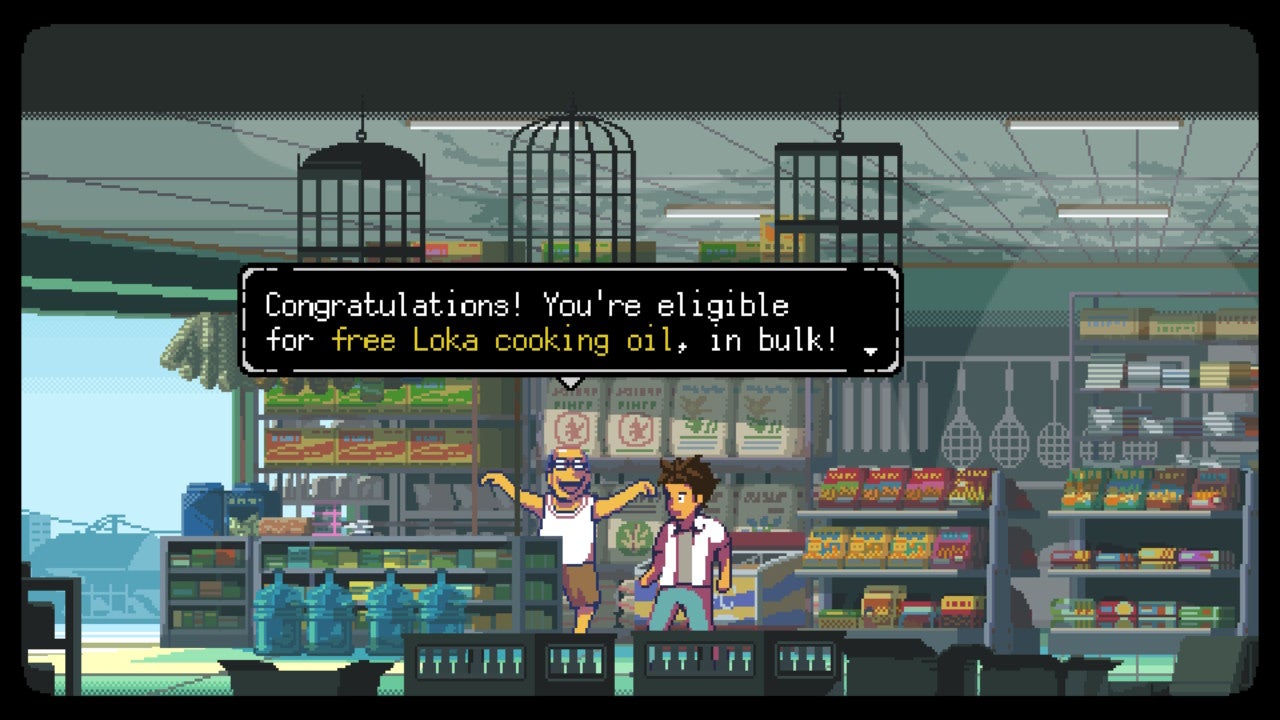

After a big, frankly traumatic prologue that ended with one of the most memorable first-person sequences I’ve ever experienced, Unbound Space settles in as a sort of slice-of-life narrative adventure, following a teenage boy in the ’90s Go to school in Indonesia. Its setting is a blessing. The country town you jog in is quaint and otherworldly, with a few connected roads featuring nostalgic everyday life – food carts, convenience stands, a few stroll ing locals – but standing in isolation against the backdrop of a bubblegum pixel art skybox Down, like an old-school western movie set, two-dimensional and temporal.

For many players, the familiar signposts of adolescence — first dates, school reports, Game Boys, parents — will anchor you in a place so specific that you might find it refreshing. For Indonesian players in particular, there seem to be plenty of references–traditional music, comfort food, historical festivals–while its more explicitly supernatural elements, of which there are many, play a role in unbinding. That’s really the heart of A Space for the Unbound: the familiar and the unreal mixed together to knock you down and throw you off guard. The way developer Mojiken manages to cross cultures is remarkable, making something so specific to a place and time feel so universal, so gorgeous.

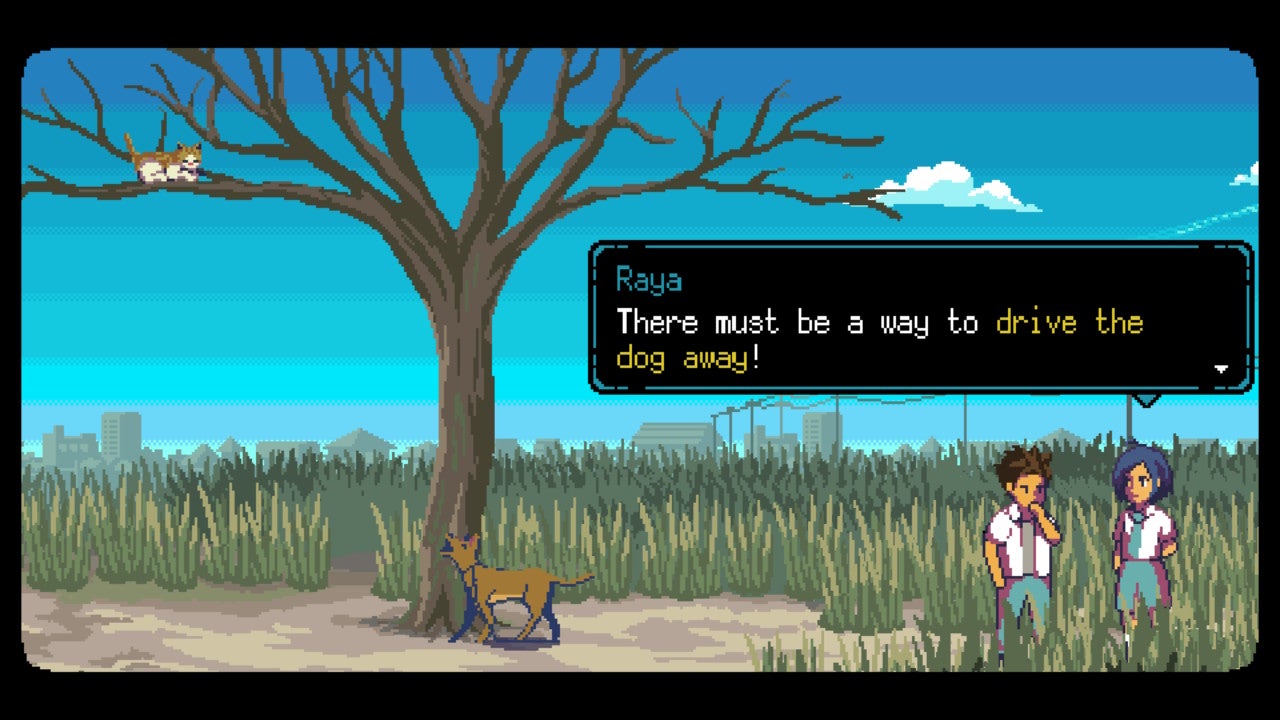

Sometimes the purpose of the mundane is to fit you into the world, to lull you into a dreamlike comfort, but it drags you down. A large part of A Space for the Unbound, the hours after the opening credits, is what you could call storyless. You go to school, but your girlfriend wants to skip school, so you have to complete some small tasks to find your way out of the school. A running dog is in the way and it is chasing a cat up a tree, so you have to complete some missions to rescue the cat and catch the dog. You need to bake a cake, but there are no ingredients, etc. For a brief moment, it can feel directionless, with a series of short-term goals put off by menial tasks that are always in groups of three. Eventually, though, it clicks.

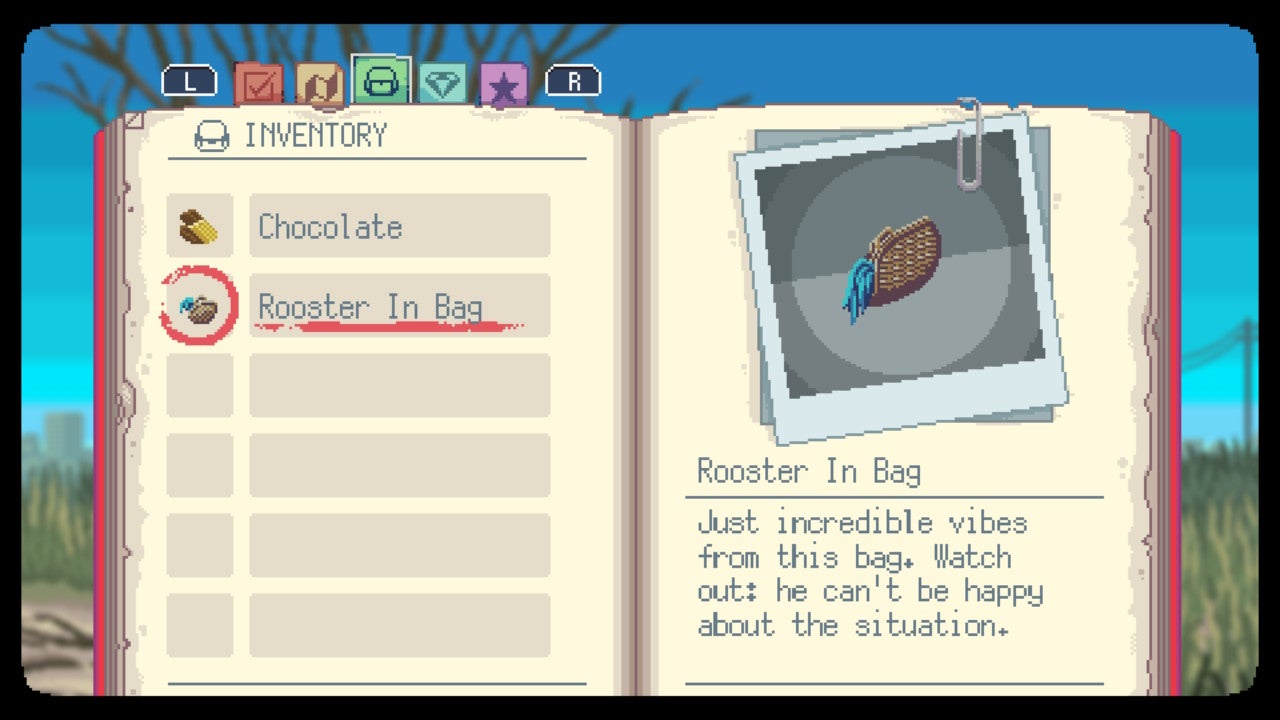

The trick of A Space for the Unbound is a mechanic called Spacedive, where Atma can use a magic book to sneak into the minds or “hearts” of stubborn people who are trying to get in your way, rearranging their minds to change their minds. Again, this often involves extremely simple puzzles that strictly adhere to the rule of three, but they gradually become more, if not more, complex. You’ll dive in and out of people’s minds, into thoughts within minds, into timelines within timelines, collecting objects from the past and placing them in sockets of minds. It’s also pretty fun at its best, referencing Street Fighter combat – you learn it from an arcade cabinet and a shriveled, if downtrodden teacher who can’t pull himself away – and many more Spacedive puzzles The title lets you gather evidence for Ace Attorney-aping courtroom melodrama.

Beyond that, you’ll collect bottle caps, fill out a mysterious storybook-cum-prophecy book, overcome your nightmarish obsession with cats, and laugh, if you’re anything like me. A Space for the Unbound is quietly funny when it wants to be, with dry little one-liners from townspeople peppering you with humor when you least expect it. In many cases, you’re deeply, perhaps profoundly, moved, especially by a broken climax near the end of A Space for the Unbound. It’s a deeply sad story, you’ll find out — the story itself, I mean, no matter how it ends, I’m not going to spoil it. That’s just the nature of the world of A Space for the Unbound, its swelling, unbearable claustrophobia, sense of panic, inevitability, resistance, comfort and existential danger, blurring of the real and the unreal. The game is messy, and it gets messier as you get deeper. Chaos is the point. This is not a tidy topic, and there are no tidy answers. But step back and look at it as a whole, it’s magical.