I don’t know if you’ve ever used oil paints, but the point of them is simple: you can move them almost forever. Oil takes a long time to dry, which is really annoying if you’re happy with what you’ve done and want to varnish it. But the upside is definitely full of upside — its front end is full of upside. You put paint on the canvas and you make absolutely no promises about anything. Over the next few hours and days, you can take a brush and move it around, blending, reshaping, reworking, and completely changing anything you touch.

Anyway: I think Jeff Minter handles the code in a similar fashion. That’s part of why his games are hard to understand at first, or more precisely why I find them so easy to misinterpret. Oh, and the space giraffe is stormy again? Well, maybe at first, but that’s really how he started with the canvas. Then he started moving things.then he started to move That things around. Then he’s remodeling, reworking, seeing what satisfies him and rebuilding everything around it. Minter has said before that he doesn’t see his job as rendering a set of design documents in code. Looking back at his games, there’s always a starting point – a template, usually an existing arcade classic – and then changing it by moving all the paint around until something new emerges.

I think the same is true for Akka Arrh. In fact, maybe it was never quite as real as Akka Arrh. Minter describes his latest arcade game as a real-time strategy game, or even a tower defense game where the player is the tower. One more thing: it started its life as an Atari design, but never quite made it into production. As always, when I started playing Akka Arrh, I was wrong. Oh, I said, it’s Tempest again, only upside down. You are at the bottom of the well and you are at the top. Of course, I forgot about the process. Remodeling, rework, serious work, seeing something pleasing from one moment to the next.

The rewards of working this way cannot be overemphasized. Akka Arrh takes a long time to click – at least for me. This is because I was looking for an easy way and there is no easy way here. (That said, I do recommend switching the default one-button controls to a two-button option.) But when it does click, it takes clicking to a whole new level. It hits deep – subcutaneously? It was deeper—a thrill I felt in my bones, in my marrow. It’s a game that packs a lot – more than any Minter game since Space Giraffe – and it gives you a surprising amount of things to keep in mind as you play. However, as it slowly transformed in Minter’s mind, eyes and hands until it reached its current state, its complexity is waiting to melt away to reveal something that feels pure. pure understanding. This game puts you in the mood.

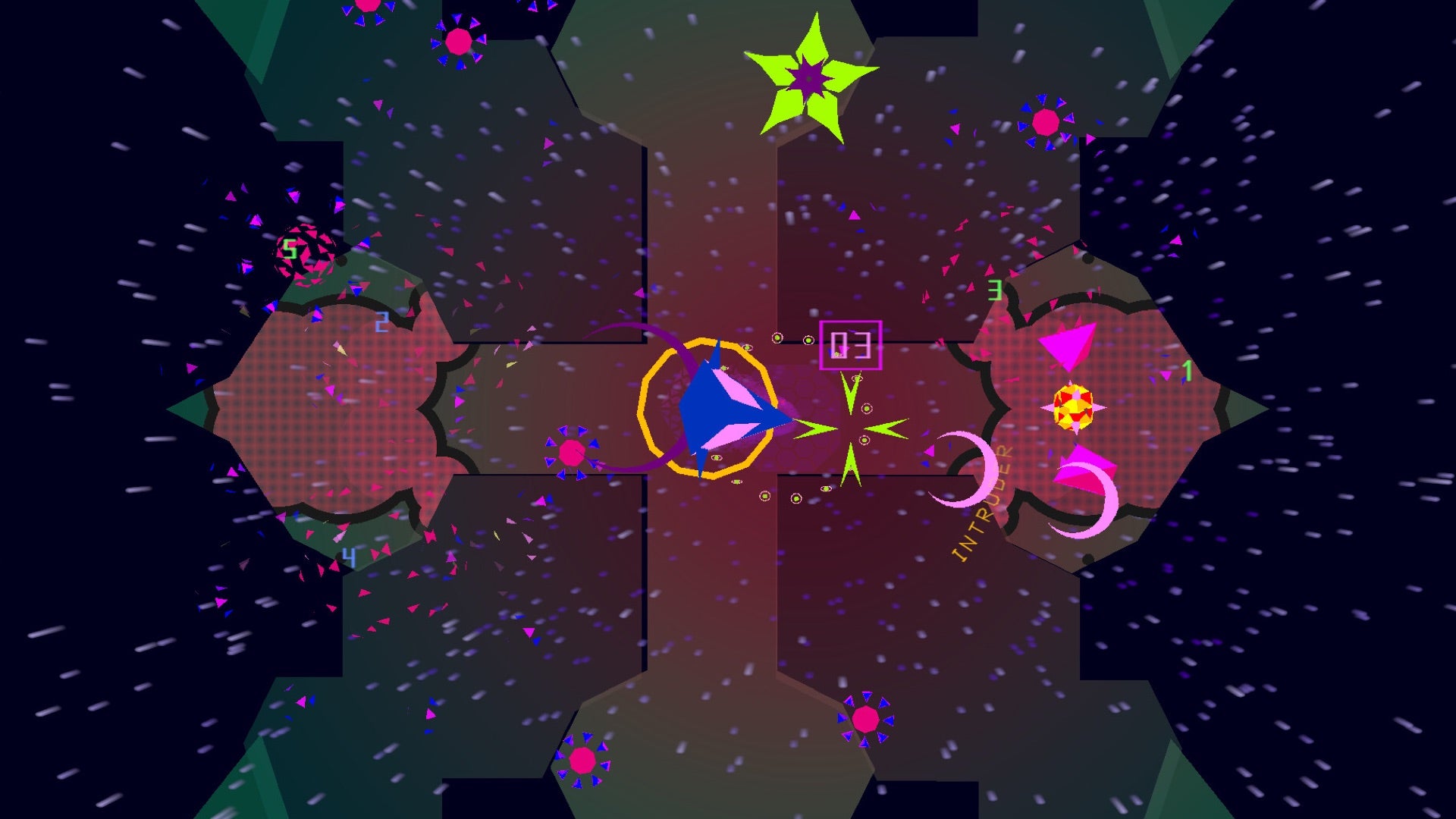

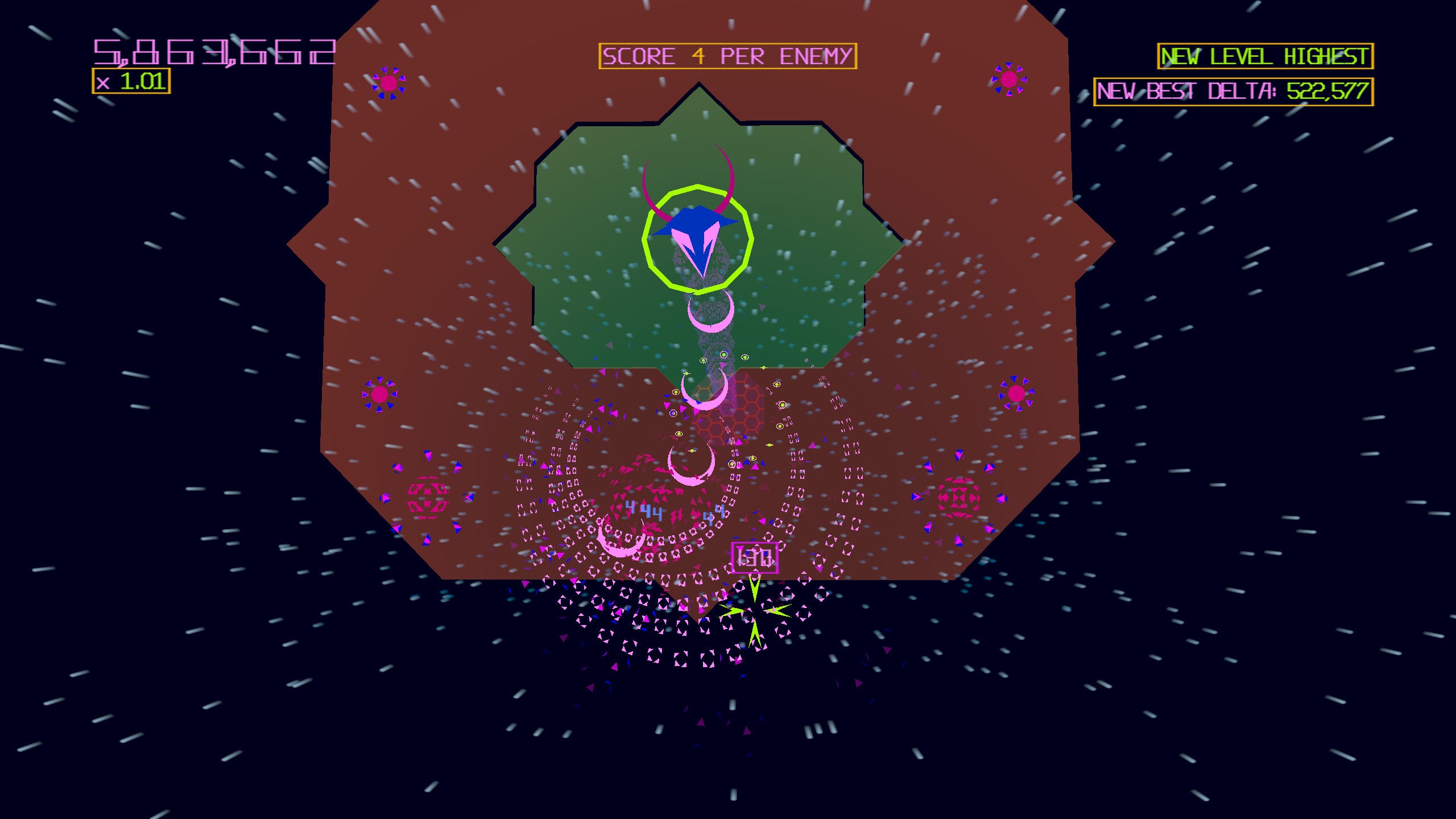

God, how to explain this? You control a ram’s head tower in the center of the playing field, and a playing field transforms from level to level, twisting between flower shapes, medieval bosses, crosses, and often growing different heights as the platforms progress— – Different levels of management. Enemies attack towers and try to steal the pods you have there, which count as your health. All pods gone? You are dead. Anyway, stay with me: you can kill a lot of these enemies by throwing bombs at them and then trapping them in the shockwave rushing from the bomb’s connection point. Any ground enemies caught in the shockwave will voluntarily die and trigger their own shockwave.

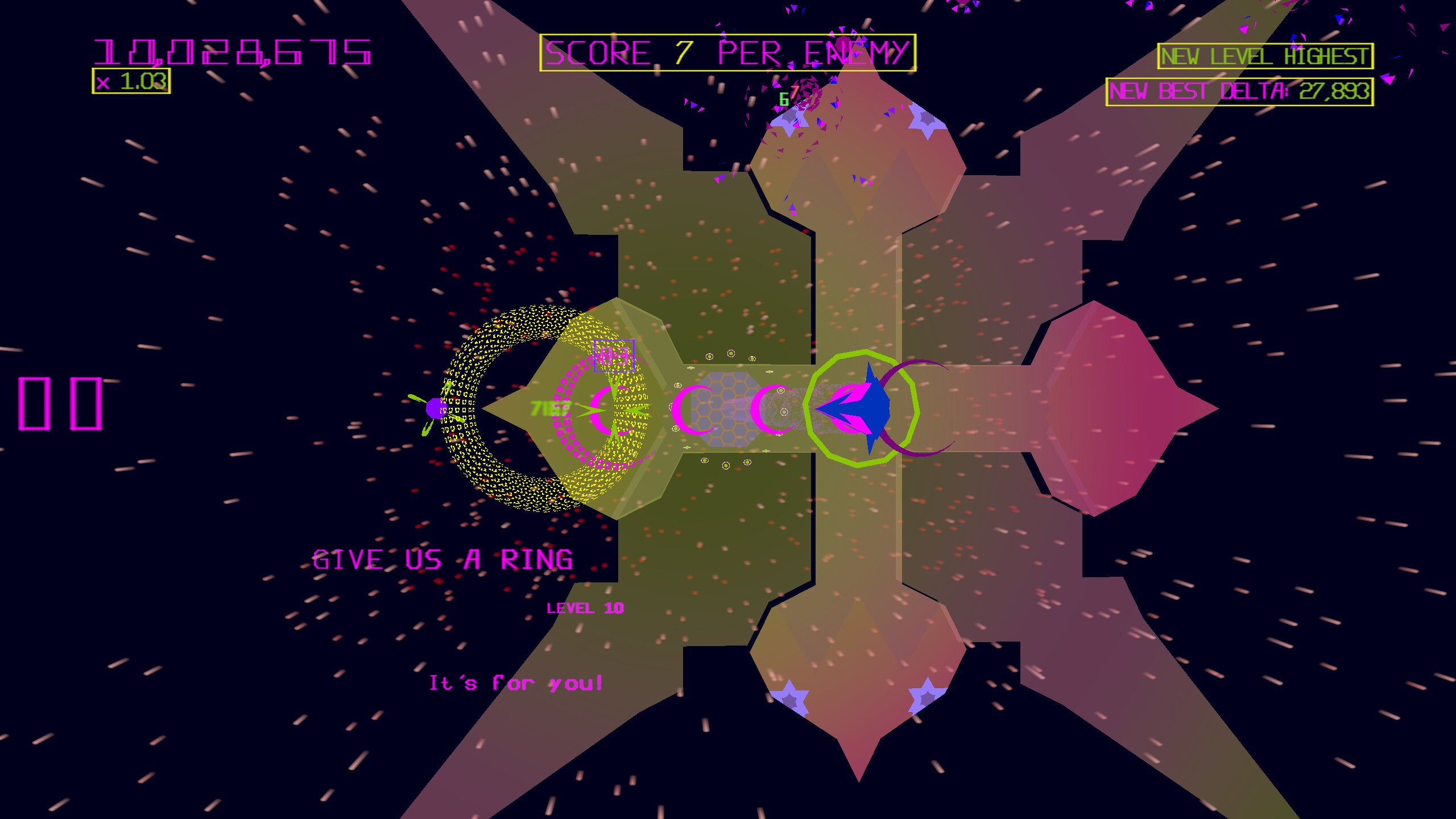

chain! A portfolio is starting to build, the key is to keep it climbing. This is how you get high scores! You can drop bombs all you want, but they will all reset the combo, so use them sparingly. Akka Arrh wishes you grace. Find that perfect place, that perfect moment, the perfect configuration of incoming enemies to create a never-ending wave of bombardment.

More, though. there are more. First, when the game has different levels of platforms, bombs will only clear enemies that fall on their level. And then—did you see that? – Some enemies are not affected by bombs. These enemies need bullets, which you can shoot in all directions from the rotating tower.bullet – did you see that this future? – Earned by enemies you kill in bombs. So bombs are infinite but should be used sparingly as they reset your combo and bullets don’t reset your combo but should be used sparingly as they are not infinite.

From this design, a lot of magic happens. At the simplest level, you’re given entire stages designed to be solved, and completed by simply dropping a single bomb, which leads to endless rippling consequences. It’s chaos, but it’s actually choreography. This is elegance. But Akka Arrh is great because it acknowledges that you can be inelegant at times, and it gives you tools and consequences. You collect tools like power-ups, or in a lucky moment, a bullet goes exactly where it’s supposed to go and saves you from disaster. The result is like that horrible feeling when bulletproof enemies swarm over you and your pod and you realize you’re out of bullets and you’re wide open and it’s all your stupid fault.

fault. Let’s go a little deeper here, because the more I play, the more sure I am that management errors are at the heart of this game. It’s not about pure success, it’s about knowing all the ways that can lead to failure and avoiding them. It keeps prompting you: End the chain by dropping another bomb, and the game literally booes you. Or at least a sympathetic groan from the unseen audience. Complete a level but can only fire too many bullets? You will be penalized for not sticking around enough. If your base is invaded, your bonus will disappear. Succeed, the game tells you, by closing off these basic avenues of not being successful.

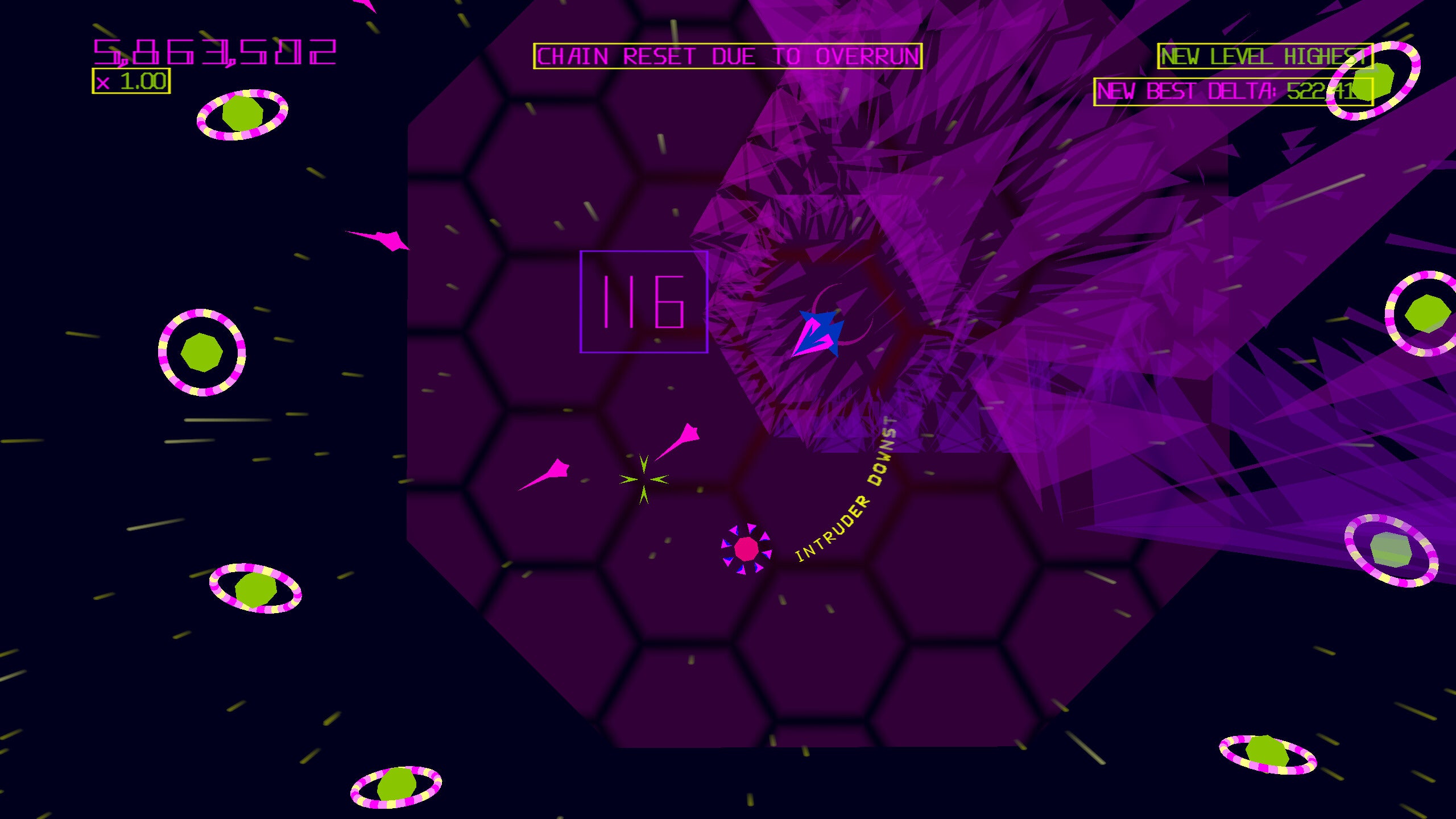

The more you play, the more you’ll discover the gags and twists and moments of brilliance that emerge from the central idea. There’s an incredible amount of Space Giraffe, there’s Tennisy enemies trying to get you involved in a volley, and all these sound effects – bells ringing, cats on the piano – trying to get you into certain events. But still at its core, the rigor that makes it so replayable: everything counts here. You have to keep an eye out for different enemy types, different game levels, the state of your various resources. You even have to learn to go downstairs – during those invasions, when your tower is overwhelmed by enemies, you have to descend this horrible pipe to clear your base close-up, firing on any enemies that get too close. It’s scary and brilliant – a scare that needs to be in two places at once. For all its other advantages, the Akka Arrh does a good job of simulating the feeling of ringing your doorbell, like you’re taking a shower.

It’s all delivered in classic Minterania, too, from the sitar and clip samples on audio to the witty, often helpful text and strobing Robotron colours. For all the digital abstraction, there is a strong sense of privacy about the inner workings of the body throughout the game. The basic enemies look like flu viruses covered in spike proteins, while the enemies that then swim around in swarms are a bit like glial cells. I’m guessing all tower defense games are about homeostasis and the immune system, but it’s hard to imagine this intense battle being fought under a microscope.

How to find the right words for Minter’s work? Sure, his game coined its own terminology—in Space Giraffe, you can perform a bull run, or prune a flower—but after playing a few times, I’ve reached for a microscope, or struggled to get the most from an emerging magpie. Selected from the allusions. You know, Every Extend with its ever-expanding borders and chains, Robotron again with its swarming horror of differentiation, and, yes, Tempest with its central pipeline. guard? Why not, it distracts you like a sushi chef, on top of that there are some crossword puzzles that I can’t quite get my head around, you sometimes feel like there’s a single solution to each level, the spaces are Secret machines are waiting for you to find the only correct way to activate them.

All this is to say: cor. Cole! I know I’m still in the early days of Akka Arrh, not just playing it but figuring out what it is and what I like most about it. I guess it’s no surprise, since it took me years to get my bearings on Space Giraffe, to start decoding and translating the unspoken joy I found in that 50 MB package. But that’s part of how these games are made, right? Part of the benefit of moving paint. Turner painted like this; there is a wonderful story about a child watching him paint, and the canvas is just a flow of colors all morning, and then suddenly there appears a sailing ship, complete with intricate rigging. This is Minter, too: a mixture of thoughtfulness and decisiveness, perhaps the artistic tradition to which Minter belongs most. Here, a digital romantic is fully revealed, and what he can show us is almost overwhelming.