Memory is impossible. It is invisible, but all-powerful. It’s like living with a ghost, but the ghost is Arnold Schwarzenegger.

If I were making a game about my own memory, my own experience of interacting with memory, I believe it would be the worst game ever made. An open world event, but an endless glitch event. The landmark disappears and moves. The same journey may take hours one day and seconds the next, and when you arrive at your destination, it’s a whole different story. Wherever you go, you are always at the center of the map. I don’t want to play this game.

But what about games that explore other people’s memories? What form will that take? What could be wrong with it? I think in hindsight Zhuge Liang tried to answer the first question, and it also provided a lot of answers to the second question.

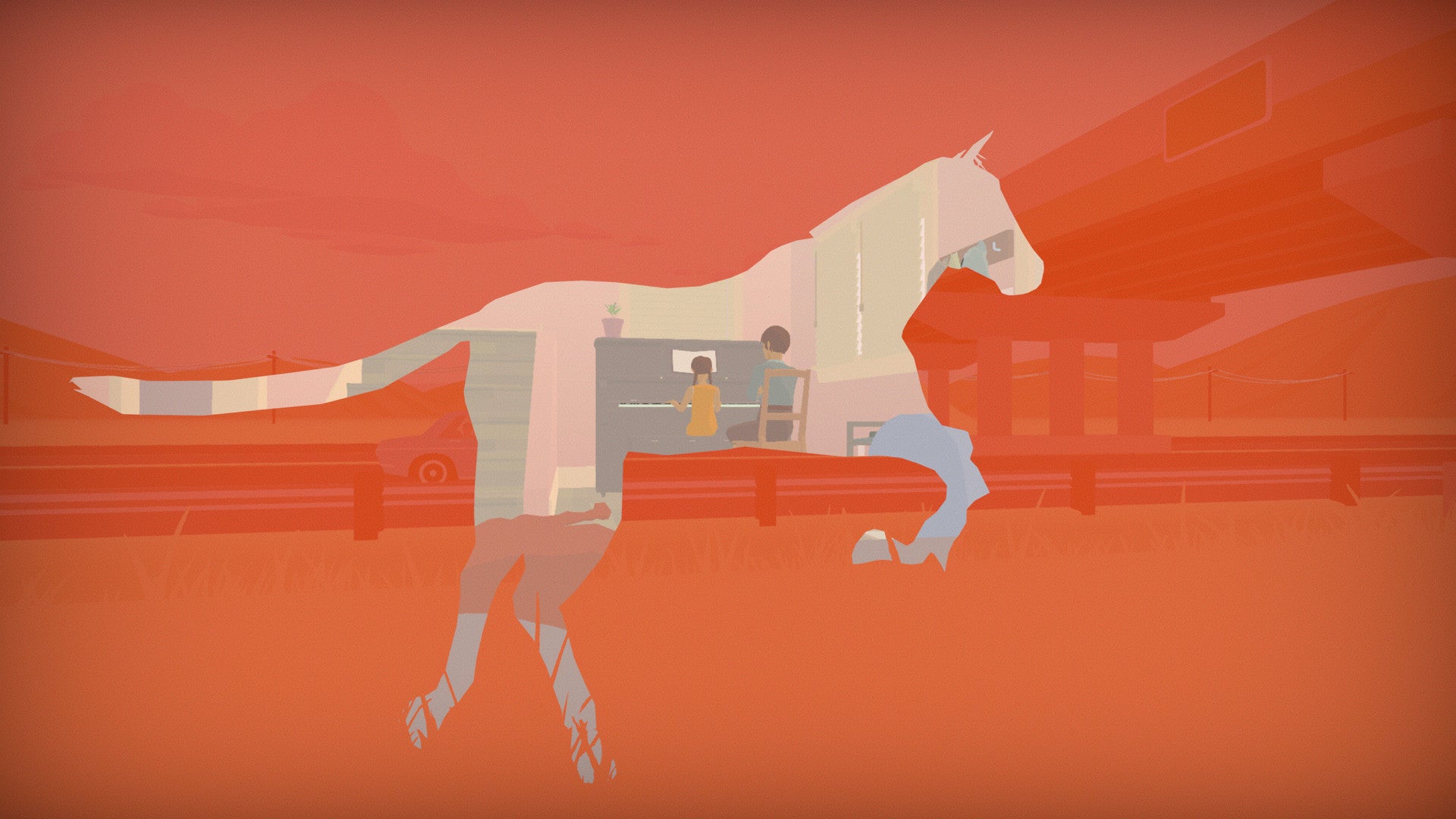

Hindsight is the story of a woman returning home after her mother’s death. She packed her mother’s things, moved from room to room, and left. That’s a story. Another deeper story is her riding the heat of memory as she walks through the house: the distant past hypertext itself comes into view, simple paths are suddenly blocked, time bends, then loops, then spirals.

It’s pure montage – a series of dioramas delivered in solid colors and simple 3D models, the textures of the whole thing are carefully bleached and too special. However, the form of this montage is more complex. I would say hindsight is taking turns trading, ghosts and windows.

Cornering: In most dioramas, you move the camera around a fixed point, looking at the scene and looking for things to click that might move the scene forward. Some are ghosts: the protagonist is clearing a bookshelf, but the ghost by the desk hints at her next destination and next mission. Others are objects—bags, tire swings, tons of knives. Click on the object, or move around it enough, and it becomes the window for the next scene. Click the window and the story continues, but you are elsewhere.

Hindsight, I think, is how memory makes these weird little jumps. If you’ve ever stopped in the middle of a sentence wondering how you’re talking about Reece’s Pieces, when you start wondering about the weather, your way back reveals all the quirky, individualistic logic of these hops. This then that and this. Our conversations are stepping stones.

So yes, Zhuge Liang pointed it out after the fact. In one scene, the kettle reveals ancient memories of the family in the kitchen. It reminds me – oh my gosh, memories are never easy – that the smell of gas stove and hot jam always takes me back to my British grandmother’s kitchen. All I saw was a toaster rack, and I was lost for ten minutes in somber reverie. Luckily, really, toaster racks are falling out of favor these days.

But Zhuge Liang often ran into trouble afterwards. On the one hand, you move the camera with one stick and a nasty, slow cursor with the other. Why both? Both you’re basically doing the same thing – looking for clickable objects – but now you have to do it twice, move the camera, and zero out with the cursor.

Some of these clickable objects are very small – so may be cursors. But looking for the equivalent of a scene transition trigger isn’t the best game anyway. We’re not in the realm of skill games, and more importantly, the game seems to want to flow — from turns, to ghosts, to windows — the way memories flow, taking you from one disguised twist to the next. Looking around for triggers kills flow and makes the game feel unstable.

Sorry, yet another question. There are lovely interactions here – you’ll move books in bookcases to reveal scenes hidden behind them, you’ll combine raindrops into a mirror and move clouds from the sun, but as you work, between memory and memory Navigating the fringes of reality, you’re not alone. Hindsight has a protagonist who is also a narrator, so as you switch between these beautiful, composed fragments of time and thought, you translate the subtext into text and slap on top of everything.

The narration was good, but it felt like a team lacked confidence and they couldn’t tell the story with the images, where the story belongs. Usually it’s an annoyance – the music also seems to intentionally emphasize things too much – but sometimes it really hurts things. Rather than making things feel more personal, it makes the sequence generic in some way. Instead of pulling us in, it pushed us into the heart of clichés and actually pulled us apart.

This also weakens the player’s character. The most interesting work in this game is all the writability – navigating emotional scenes, shuffling and choosing possible interpretations. How do these people feel? What will they do next? How could they possibly misunderstand each other? When the voiceover pops up to answer these questions—”I’m hungry for praise!”—it simultaneously inspires any amusing ambiguity. It feels like a lie: how often do we feel only one thing, without internal contradictions?

At worst, the narrative means your character becomes purely technical, purely physical—you’re moving the camera, selecting parts of the image, packing up your mother’s house and loading boxes into the van.At this point, I start Play Play rather than engage in narrative – I’m more likely to look around for glowing objects than around the house for a specific item that the story logic calls next. At its most worrisome moments, I started to hate how this narrative took away the power of the story.

But not always. Sometimes, in hindsight, Zhuge Liang remembers the effects of silence, especially near the end of the sequence, where imagination literally spills into memory and threatens to sweep everything away. The game is blooming. I was left to pick out images and think about how fantasy and memory work together and often destroy each other.

The more I played, the more I managed to understand the things Zhuge Liang did really well in hindsight. That said, over time I’ve come to focus on what the game is saying rather than the self-engaging, self-defeating way it sometimes tries to express these things. Or, maybe, in order to flip it in a way that feels honest, I stopped trying to be smart about what I thought the game was doing wrong. My own narrator took a break.

“Sometimes, with hindsight, this charming and embarrassing game, really soars”

What follows is a simple but powerful story about a child raised by a charming, incomprehensible, and often silently punishing mother. Daughter and mother clash. The daughter wants something, the mother wants something else. Daughters want to take risks, while mothers are cautious and – worse – preachy when things go wrong.

Of course, it goes both ways: the mother wants her daughter to know about her own heritage, about her life in Japan before moving to America, and the daughter feels guilty for thinking it’s a chore. (The game is the most precise and penetrating in examining the subject. The experience of being raised by parents from another culture rippled in hindsight in dozens of ways that I could appreciate and learn from, and very There are probably dozens of other ways I can’t see. It’s a generous and illuminating game in that regard.) Mother and daughter are at odds on many fronts. Maybe that’s what the narrator is really trying to say – all these monologues, no dialogue.

It can be very effective. Now, back in my daughter’s sterile apartment, it’s clear to us that something went wrong along the way: the sheer grey walls and empty space seem to say it. This is your own memory, a reminder of your own fears. Inevitably, it made me think about not just the people in the story, but the daily challenges of parenting on this side of the screen—how to show interest without causing stress, how to listen to the passions of others, and not Just share your passion. Playing this game, at least for me, reminds us that every parent is also someone’s child – I know it’s pretty obvious, but just write it down. No wonder we are often pretzel of emotions and doubts.

Sometimes, with hindsight, this engrossing, embarrassing game can really soar. The daughter is taking piano lessons – her mother wants her to play – but her mind is elsewhere. I opened the shutters nearby and we sat in the car, cruising the countryside. Parents at the front, daughter at the back, fascinated by a galloping horse that no one is looking at. It’s passion, it’s private, neglected passion. No game can play with this material without presenting something memorable.

“We saw the world once in childhood; the rest are memories,” the poet said. I admire this phrase for its ability to zero in on our limitations, even as I question its airlessness and certainty. I do think, though – and I think Zhuge Liang solved it with his own flashy elbow in hindsight – that childhood is something we try to solve for the rest of our lives.