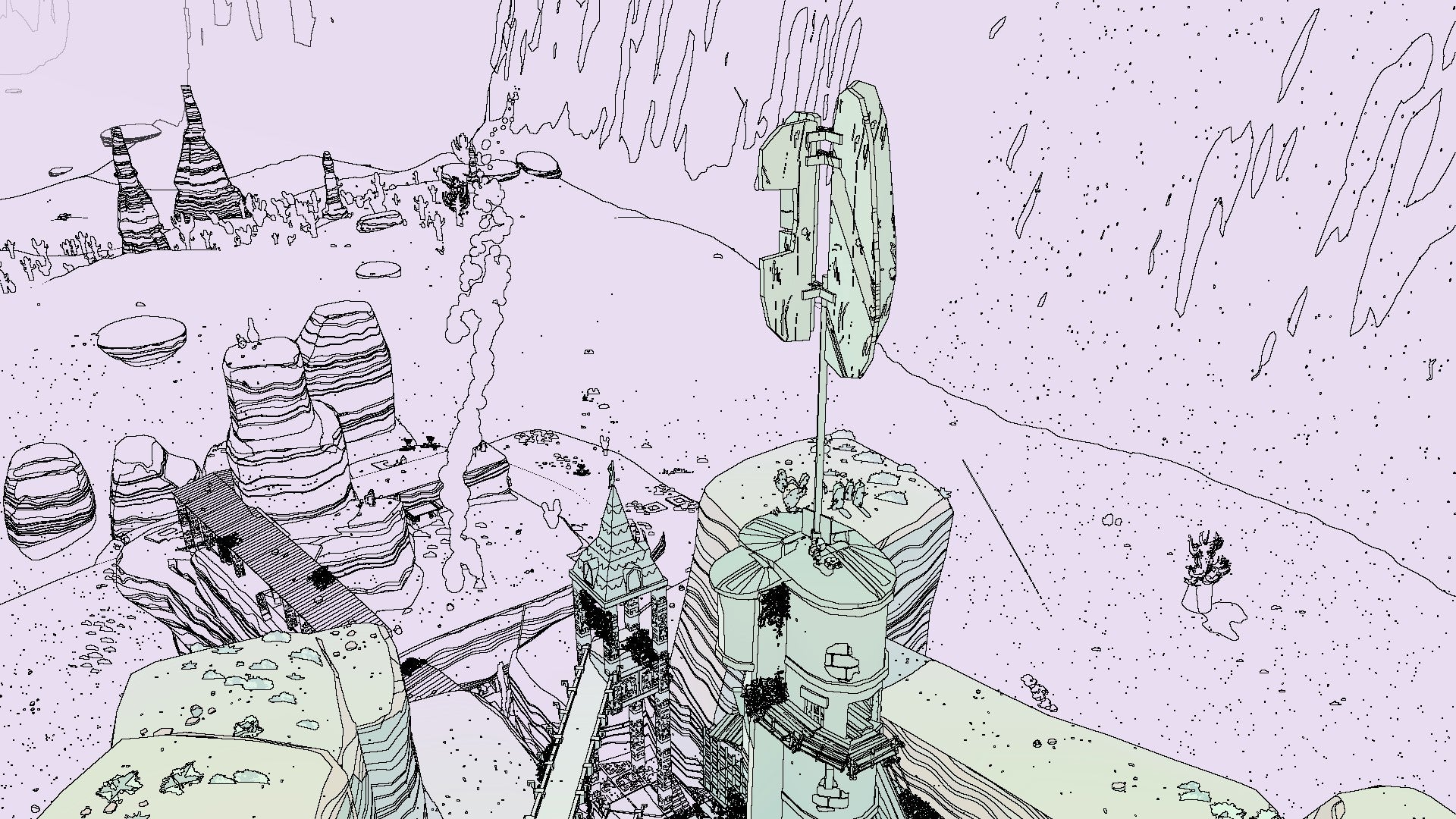

It’s interesting to see how full the brain is. Sable’s art: You could say, hey, it’s the French artist Moebius who once made Silver Surfer such a graceful, solitary being, a swift, gleaming will that galloped down the canyons of Manhattan above the bombed-out. Or you can talk about the fineness of the lines, the soft colors that flicker slowly, the use of shadows sparingly.

But these are just separate parts, and the mind will fill everything anyway. It compliments the emptiness, giving this desert landscape with its dappled land and Vegas carpet of bare strata an overwhelming sense of time spent. Time flies! Centuries of immersion in the ground, bleaching animal bones and blunting machinery, reveal a hard, dry world washed away by a distinct background. The swaths of sand make you wonder what forgotten lakes once gathered here. At the same time, the thin black threads that give the game its illustrative style act on the scattered dwellings, giving the stucco a powdery, urn-like feel, and the tattered sheet fragments fluttering like old shrouds.

The trees, outside the forest area, appear to be charred, with the outer bark scorched by the sun. Elsewhere, colossal things are ancient scraps, half-pipe fragments of what used to be huge science fiction. Smoke rises in thin clouds – a clue? hint? Then night fell and the sky suddenly became so dark, so blue, that the earth lost its hold in the wonderful darkness, and the stars appeared, making everything pleasant.

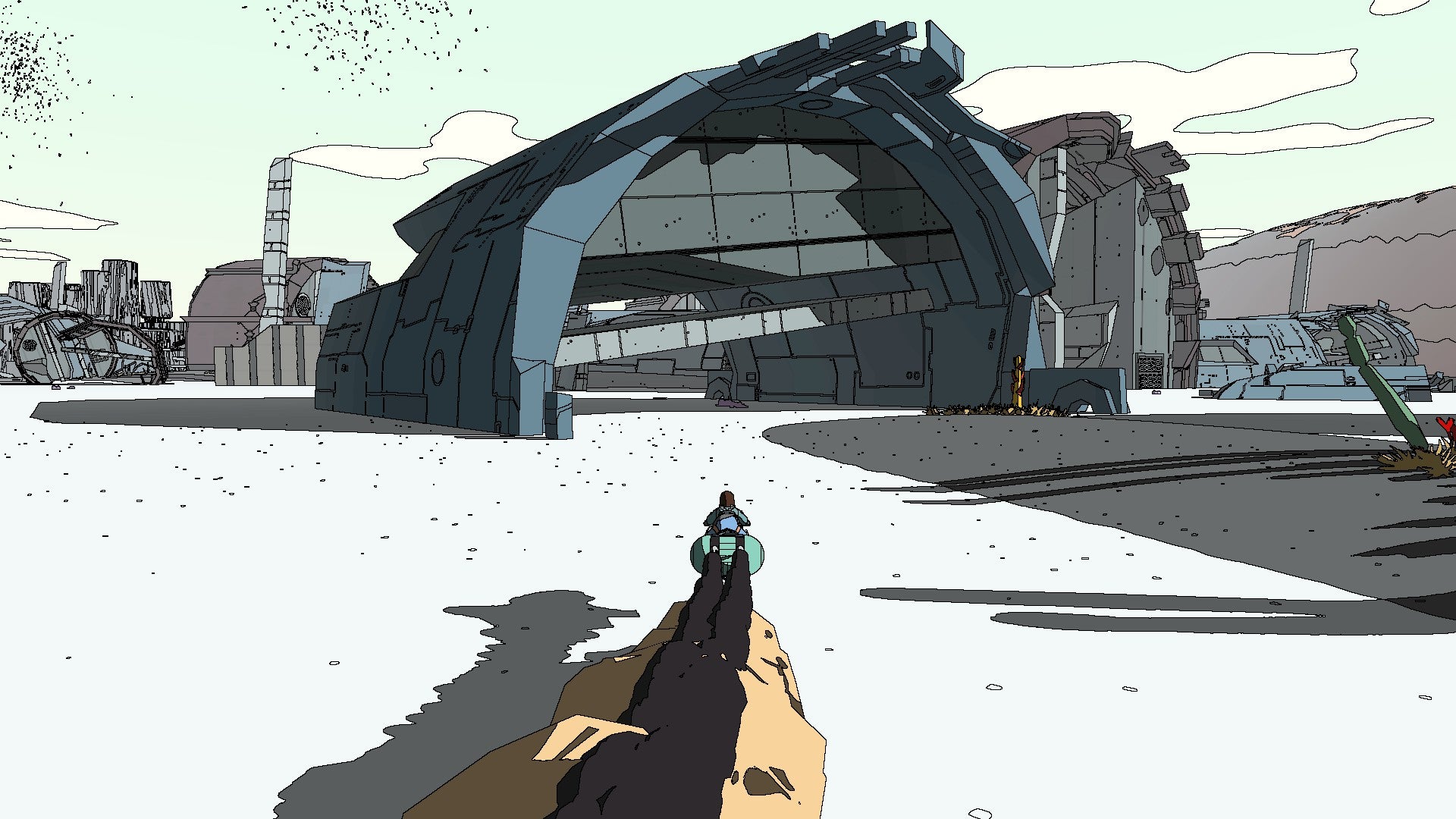

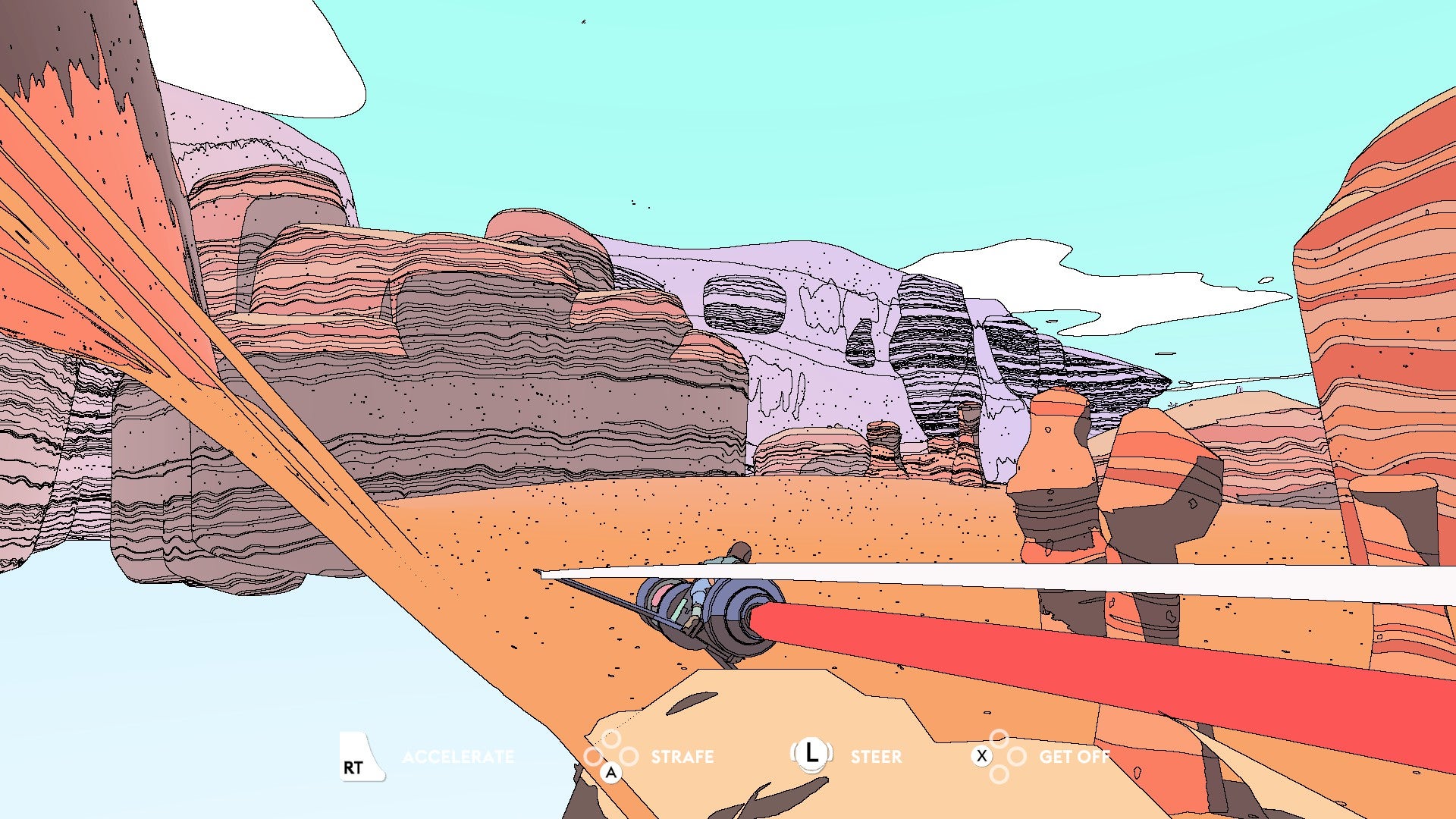

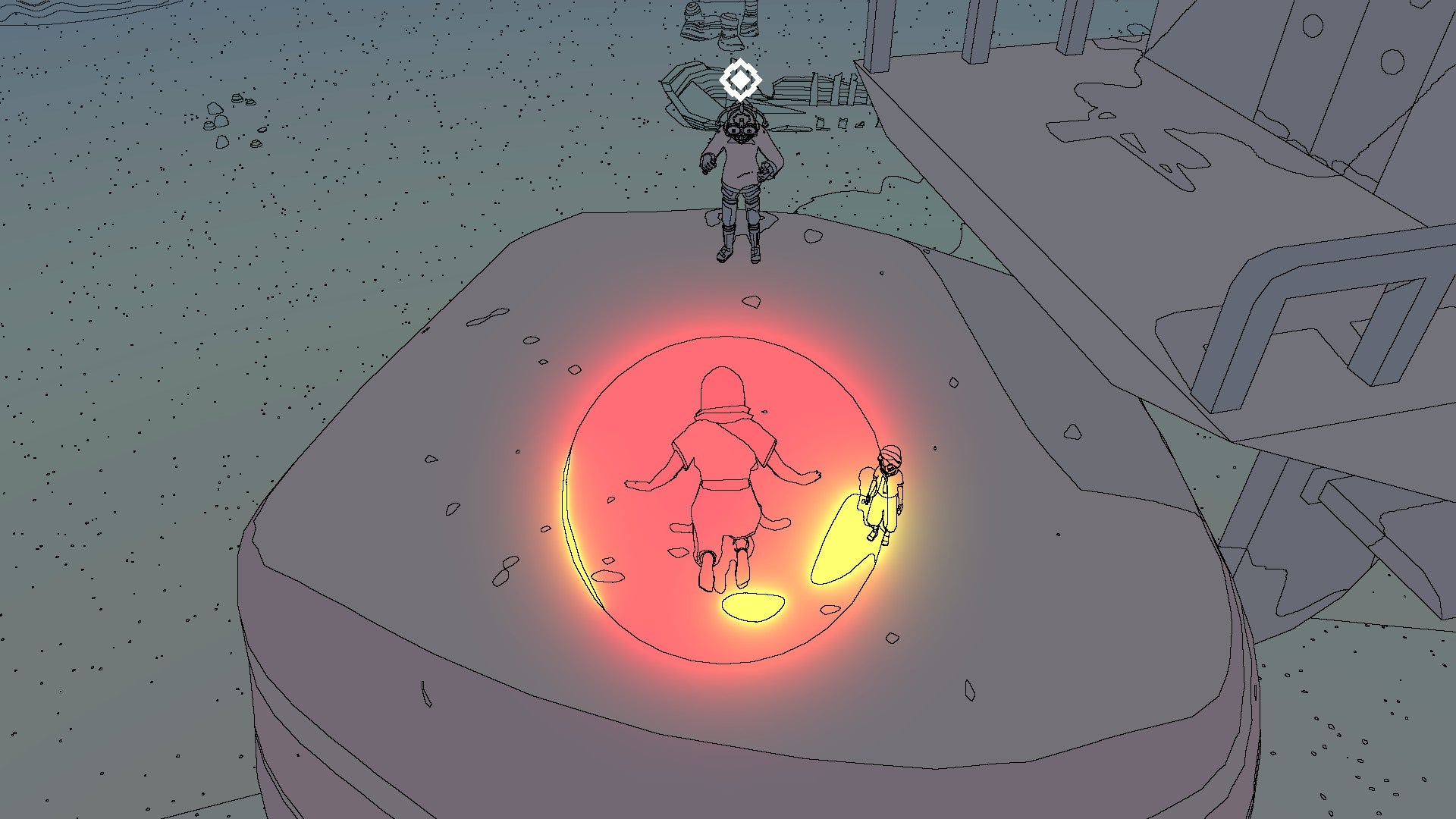

Sable is a game set in a sci-fi desert, rendered in the lines of French sci-fi, both intricate and paradoxically sparse and airy. And Sable is a character in the game, the protagonist, who has reached puberty, which means she has to ride her ATV on a journey away from home—a ritual that can only lead to adventure.

What I love about Sable – aside from the environment and aesthetics – is that the form the adventure takes is refreshing. There is a very simple guiding principle here. Who do you want to be? Sable is looking for her place in the world, so as you play, you’ll earn badges from quest givers to complete various quests. Badges represent the type of task undertaken or who set it up. Scrap collector? guards? Strange things? Buy three and you can trade it for a mask that represents that line of work. At the end of the game – once you have several masks, you choose this – you choose a mask. This is not a spoiler. The game is fairly open about its intentions. There is no fight. There is no boss. You will find that Sable has a place in the world.

I make this sound complicated, but it basically boils down to: do what you love to do, and do what appeals to you. To me, that means cartography, which in turn means climbing. Cartographers are scattered throughout the game’s deserts, always high up because they have to see the landscape. So you see them in the distance and then you have to figure out how to climb them – a climbing puzzle! Sable uses Breath of the Wild’s climbing system – an stamina meter combined with the fact that you stick to most surfaces. As you rest, you go from ledge to ledge and rebuild your stamina for the next stop.

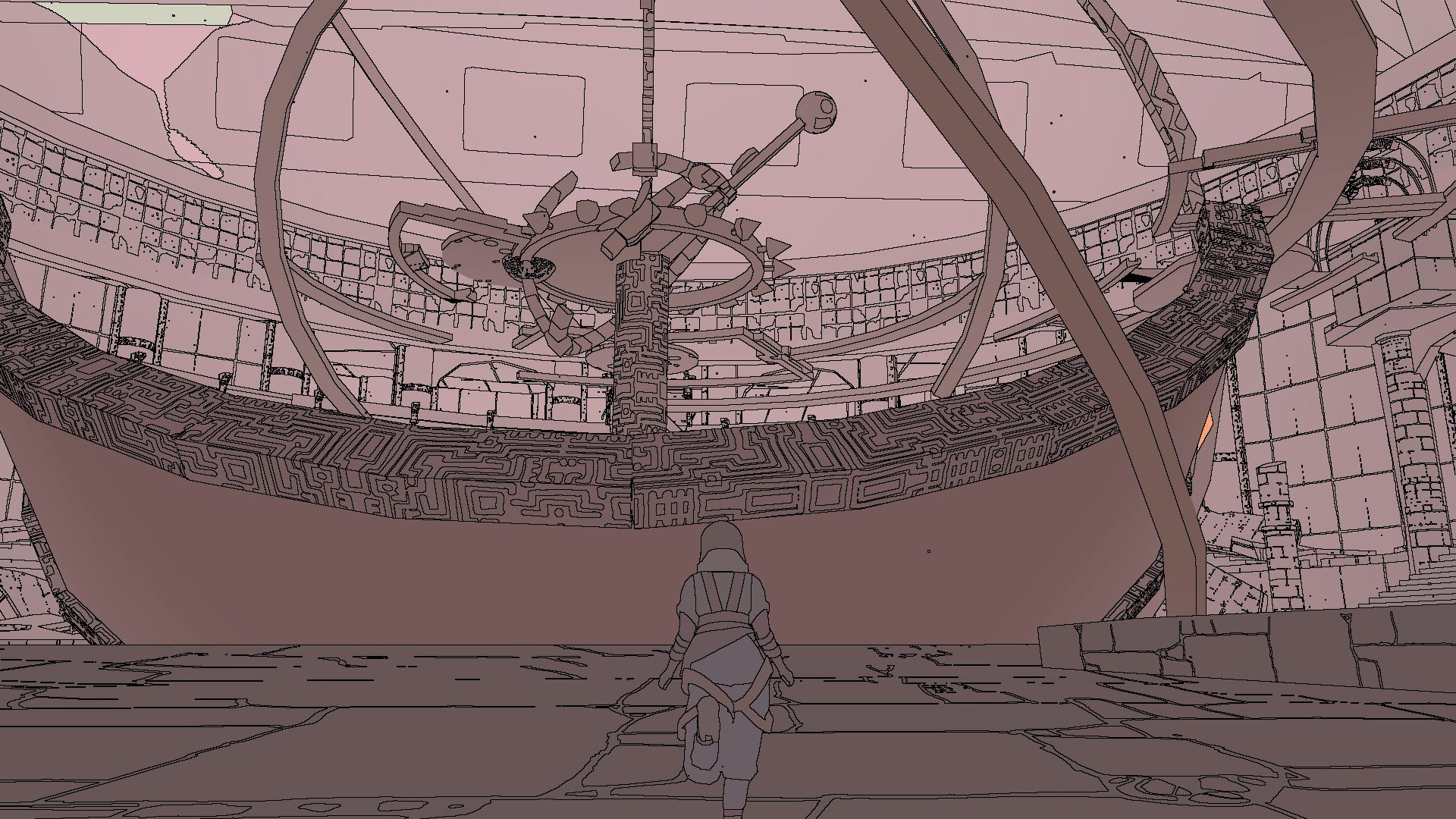

In the early days, cartographers would be on low towers or simple bluffs. My favorite moments in Sable come much later, though, exploring the outer reaches of the game. A cartographer stands on a huge piece of construction scrap – the wreck of a crashed and looted ship. To get there, I had to unravel the correct route, see which parts of the landscape would take me a little higher, and see where I could continue from there. It took me about fifteen minutes. This is nothing compared to cartographers hidden in the wilderness, perched on rocky spires and accessible only by curved bridges made of ancient animal spines, alternating toughness and fragility.

When you get to the cartographer, they’ll sell you maps that slowly fill the game’s multi-part world. But they’ll also tell you nearby areas of interest – areas they won’t put on the map for you. They’ll tell you about other parts of the world that might be close, encourage you to play games with wordless maps and testimonies from people you meet, and they’ll say, “Oh, what you want is here in the southeast, in the northern wasteland. “Northern wasteland? Here, spaces and words have to come together in your mind, like a real exploration.

One last thing about cartographers. Some people are very cheerful. After a long climb, accompanied by cheerful cartographer music, it can be a pleasure to find them on it. Some are mild, some are shy, some are grumpy, almost paranoid. They are all people, all themselves. Everyone at Sable wears a mask – I guess it’s the one they’re calling for. But the mask allows the characters to emerge more strongly in the writing, which is again deft, sparse, and the word warm, always suggesting a world of complete reality, a fragmented world, a gleaming mosaic of interactions, hidden Gold in a handful of sand.

I think I like cartographers the most, not just because of the climbing, or because they allow me to fill out maps, but also because you don’t need to be told to find them. You just see them on the horizon and want to explore. I think it’s a little bit tight in Sable: that’s what it asks you to do, do it yourself, go through the ritual, but it also needs to give you a little frame, a little push, so there are tasks and task givers that you can get I have three of these assignments.

They are good, they are really working towards the badge and mask goal. But I feel like games always want you to stay away from them. It allows you to walk away and choose who to ignore and what to give up. It gives you a sand bike that allows you to cover great distances. Just point it and extinguish trailing smoke or send out a sweet Euclidean laser beam. It gives you a filled map – filled to the point where open space is the real focus here – with icons as you find things. Good mission – go and see why the wind tower stops turning, I like that. But it’s much better to explore and travel through a bold and empty world. See a new shape appear on the thin line on the horizon, like the image on the etched sketch. Approached and found a statue, a huge bell-shaped building, a rock formation, a crashed ship. All of these things have little challenge within them, but more importantly, they talk about size and age and a certain sense of loneliness. The stuff that makes Sable awesome.

Challenges are often wonderful, though. Get three pieces of beetle dung – all right, I’ll do it. But halfway through Sable’s journey, I spotted a huge building in the middle of nowhere and waited the best twenty minutes for the landscape to align with the light so I could open a door of trickery. I don’t remember what my reward was – probably not many: a new pair of pants or a jacket. But I remember the puzzle, the way it blended into the environment, and the confident way it made me stop and notice things and wait, waiting for the sun to move, for the shadows to align, for Sable to function as a place and play — a place that is also play.

Sable is full of this. That’s its commitment to player freedom, I’ve done and watched the credits, and I still know I’ve only seen a fraction of what the world has to offer. Its emptiness somehow contains a multitude. My bike – I can swap parts and change its color. I can buy a full set of the pants I found some time ago. The lonely AI of some spaceships tells a story, and if you get access to them, you can stitch them together. There are people to see and artifacts to think about.

But to experience Sable properly, all you need is something in between—on a bike, lost in a curated emptiness, wondering where to go next. Change plans, ignore tasks, focus on the horizon. Not bad, really.