Tragedy plus time equals…myth? A cultural fascination with true crime and serial killers is in vogue, and The Devil in Me feels comfortable taking inspiration from the 1800s. “America’s first serial killer” and serial con artist may never have had the “murder castle” complete with traps and torture devices that his mythology envisioned, but that’s what The Dark Pictures Anthology did with its escape room murderer entry of the narrative.

The Devil Within Begins with HH Holmes’ famous “Murder Castle,” featuring a thoroughly caricatured Sherlock Holmes and his guests—a mischievous newlywed couple—indulging in ominous wordplay. I fail at an early heart-pounding fast event while sneakily watching my wife crumble and giggle, getting a theatrically ironic warning from Holmes: We don’t want to fall over and crack our skulls open, do we! While I narrowly avoided that fate with more well-timed QTEs, the two lovers were still doomed: they were the prologue protagonists, after all.

Dark Pictures Anthology episodes all follow a familiar setup, and The Devil in Me doesn’t stray too far from the formula. The prologue prepares you for the horrors you’ll face before you meet the group of characters you’ll pl ay as. Whether they live or die depends on the choices you make, whether it’s a slow-burn trust issue, or a split-second “run or hide.”

After the opening credits, as The Devil in Me introduces its cast, a documentary film crew begins filming a modern rendition of Murder Castle, built on a foggy island where no phone calls are allowed. (Only the mildest complaints about this arrangement, since no one knows they’re in Horror Stories, a conceit I continue to enjoy.)

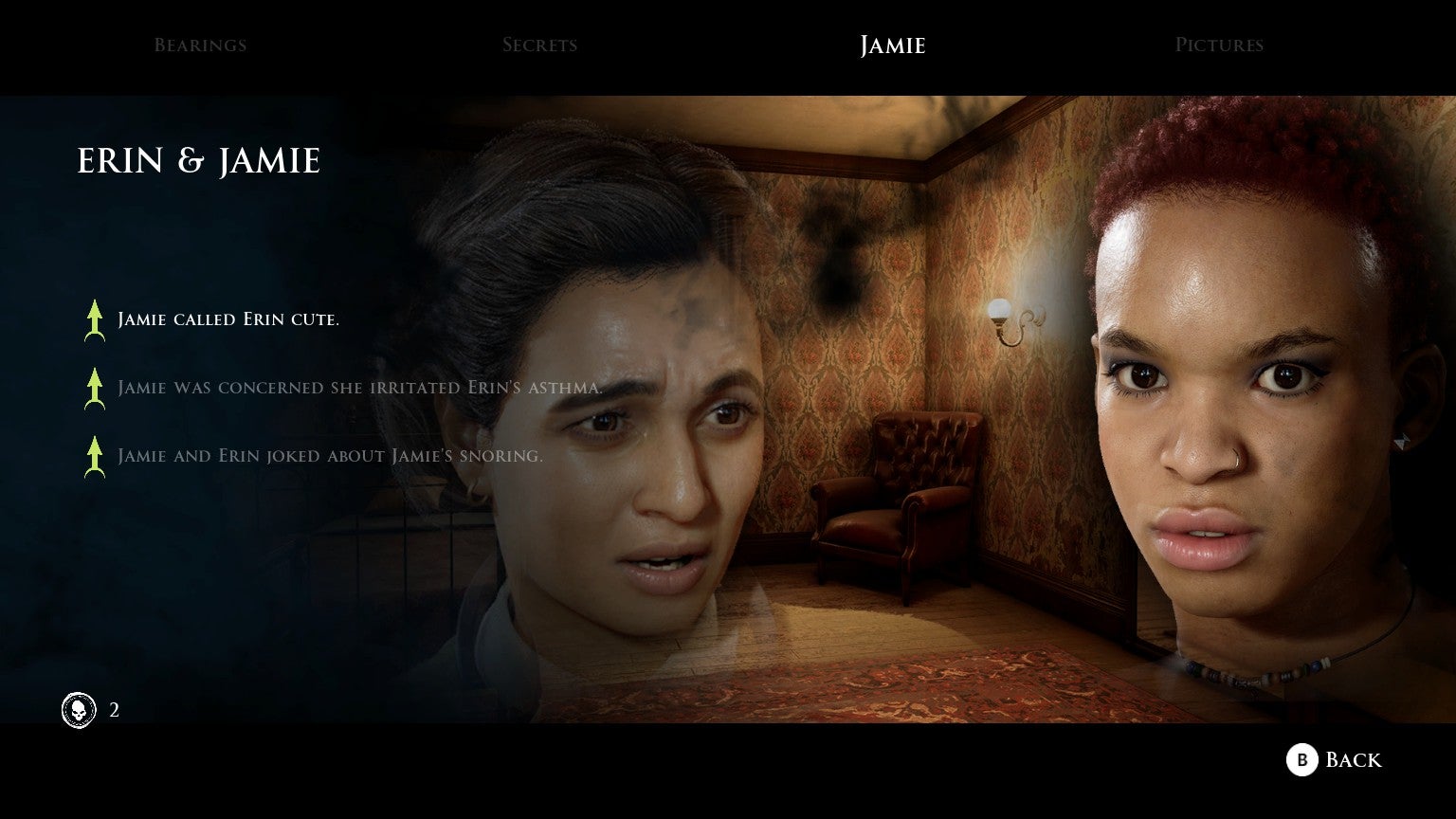

But as I learned more about the characters—the brusque director, the detached controller, the shy audio technician, the insecure presenter, and the conflict-avoiding cameraman—it became clear that my love for these characters The push is noticeably lower than I could have been in the first few episodes. I have far fewer dialogue choices in far fewer dialogues, and I maximize—or completely suppress—character relationships within the space of a scene.

Frankly: One of my favorite things about horror is watching people make poor decisions because they don’t know which type they are, or because of their own horrible flaws and impulses. Horror creates a particular kind of disbelief when people run up the stairs when the killer shows up at their front door, and I love it because it makes me cringe, or want to look from behind my hands.

So when Director Charlie is lured into an obvious trap because there’s a pack of cigarettes in the middle – sniping his crew all day because there’s no smoke? I like that, so technically it doesn’t matter to me at that moment that there is no other path forward. But more often than not, the way I explore a level, both in-universe and out-of-universe, is completely unmotivated.

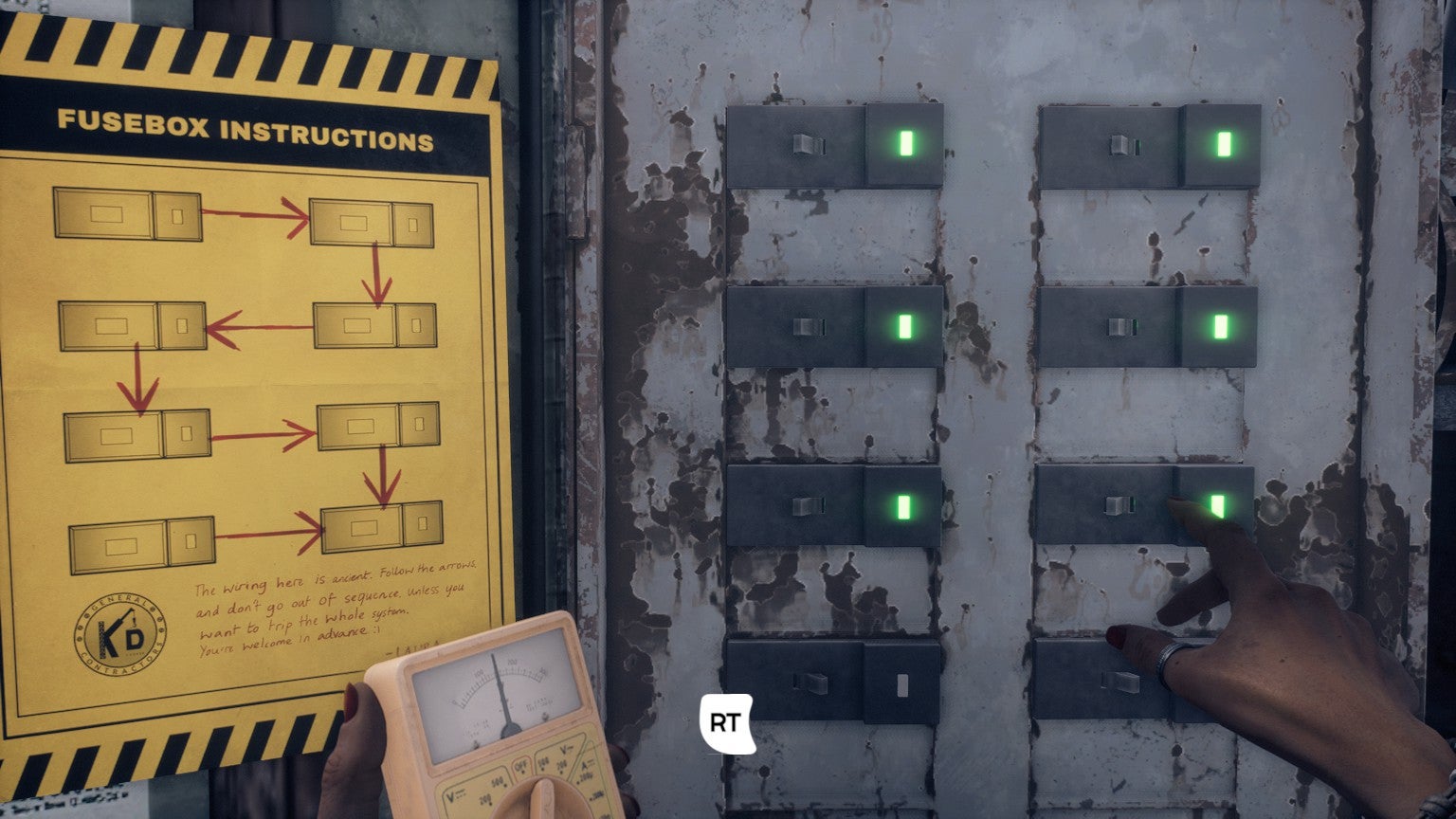

It feels like no one is making decisions at all. I’m looking for a box to move around, or a switch to throw, or a gap to wiggle, not because I need to get to the other side, but because I know how progressive it is to find the right part of the environment to interact with. The Devil Inside Me puts more emphasis on exploration, but the sequences drag on, and it feels like they come at the expense of more character-driven scenes.

However, not all exploration sequences are that slow. In one segment, I use only the red light from the camera sensor to move from room to room, and I have to scramble to hide every time the murderer and I try to cross a path. Even after a successful QTE, I still get nervous, and every time I look through the camera, I realize how much I’ve voluntarily cut off my vision. I also appreciate how granular the QTE’s accessibility settings are in these sections, because in games where it’s a binary on/off option, I often have to choose to turn them off–it takes my nerves away entirely.

Seen, seen, often featured in The Devil Inside Me. Even the way the modern cast is first introduced is through shots of testing footage as a reminder that somewhere is watching. We zoom in from the actors’ professional experience to their frank weaknesses as they scrub forward, and watch their visuals unnervingly watched over and over again throughout the game.

We see both the historic Sherlock Holmes and the villains we emulate as voyeurs, old-fashioned peepholes and modern technology leaping across time. Our cast is a true crime documentary, and the parallels are obvious — especially when we see some delightfully lurid previews of the team’s work. It’s not a subtle subject (the villain’s hideout is even described as a “director’s suite”), but once a connection is made, it seems to stop there.

Even when the characters debate whether it’s appropriate to play the detective, the game wants you to play the detective. “Is he crazy, or does he have mother issues” speculation sounds like a true crime podcast — but if you want to find out for yourself, you can piece together the biography by picking all the right favorites. Voyeurism: Not good…unless you’re chasing achievement?

It’s all set for a blockbuster first-season finale, with expanded scope, bearded villains, and central questions about our investment in true crime. It’s a very B-movie because of its ambition to make “The Devil Inside Me” less good – but surprisingly those failures of that ambition make it more tedious, while Not more confusing. Chaos is Sombra’s forte — confusing characters, confusing choices, and odd outcomes coming out of left field — and it used to be part of the anthology’s charm.

While it’s thrilling at times, its bigger, better environments largely leave wide open spaces that, while beautifully rendered, also expose missed opportunities. In the end, it’s at its best when the devil in me throws anything more ambitious to the wind: hey, wouldn’t it screw up if you were being chased by an ax murderer?Anyway, sign me four more copies Those ones.