This week’s episode of All creatures great and small – the third episode of the third season, entitled “Surviving Siegfried” – offered something rare for this series: flashbacks.

The show, adapted from the internationally acclaimed memoir series by veterinarian Alf Wight, who wrote under the pseudonym James Herriot, is set so far right in the late 1930s in the sleepy English farming community of Darrowby, a fictional corner of the US Yorkshire Dales where viewers of the 21st century cows for an hour a week and replace their worries with gentle stories about rural animal care. The series centers on veterinarian James (Nicholas Ralph), who works under the watchful eye of the fastidious Siegfried Farnon (Samuel West), whom he tries to please – albeit not as much as Siegfried’s lazy brother Tristan (Callum Woodhouse). .

All of these characters are familiar to readers of Herriot’s books. But they first became permanent fixtures on the television landscape in 1978, when the BBC premiered the first serial adaptation of All creatures great and small. Calling the new series a remake of the previous one would be inaccurate as both take their own liberties in adapting Herriot’s books. But the two series have remarkable echoes in Siegfried’s awareness of the traumas of war. Two iterations of the same man are both haunted by the same righteous world-weariness, one that four decades ago would have seemed just as evident as it is today.

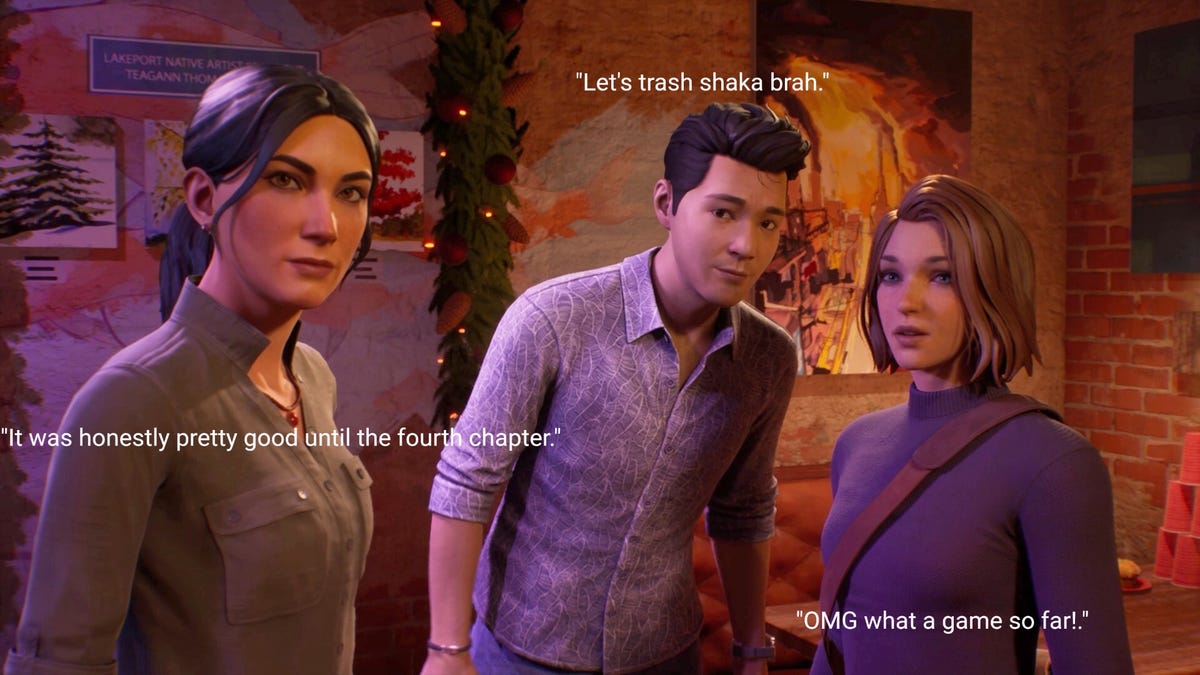

“Surviving Siegfried” transports the viewer to Belgium in 1918, a break in the series’ typical operations that underscores how present the First World War remains in the minds of the characters, who now face the Second. There, a younger version of the typically gleefully eccentric Siegfried – played in these segments by Andy Sellers and now seen around the time of the Armistice as the ceremonial captain of the Royal Armed Forces – is tasked with tending to his major’s wounded horse.

“Physically he will make a full recovery,” notes this younger version of Siegfried of the animal. But there is another, perhaps even greater, wound: “the damage we cannot see.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24372587/4311910.jpg)

Image: PBS Masterpiece

In the present of the show, another war looms, casting a shadow over a series that previously struck a soothing note of escapism. Jeeps drive past the car while Siegfried commutes back and forth between Darrowby and the surrounding farms; The previous season ended with his housekeeper Mrs. Hall (Anna Madeley) watching a Spitfire bombard the sky. Now Siegfried has been called to tend to another traumatized horse – River, who will not be ridden – and while the oncoming brutality has yet to touch these special creatures, their specter dominates the season.

“Are you all right?” Tristan asks the obstinate vet as he drives him back to River. Siegfried himself has been thrown from his horse so many times that he can barely walk, let alone drive a vehicle.

“That’s a stupid damn question!” Siegfried snaps. “Of course not! None of us is! Neither should we be! State of the damn world – there would be something wrong with us if we were!” The line fits the character and story, but might also strike a chord with today’s viewers. How many of us can actually feel good about the state of our own damn world? So the gentle posse All creatures big and small must balance its status as a comforting pick-me-up for a chaotic and painful 21st century and its awareness that the world has always been more complex than any of us like to think.

The world was no less complex and painful this month 43 years ago when the BBC premiered the third season of the original on television All creatures great and small. The season aired less than a year after Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister (the run of the original series would within a year coincide with her 11-year tenure), amid a time of tremendous civil unrest in the United Kingdom, a nation still rocked by a year of unprecedented strikes, the climax of which has been dubbed the winter of discontent.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24372585/siegfriedmsh.jpg)

Image: PBS Masterpiece

This season’s fifth episode, titled “If Wishes Were Horses,” serves as a parallel, if not the basis, for “Surviving Siegfried.” Again we see Siegfried (played here by Robert Hardy) tending to a horse, although this time the infection is in the hoof as opposed to River’s spiritual illness. Siegfried is in his element handling the creature and even leaves the operation feeling dizzy. “Summer morning in an English village,” he beams. “Nothing like that.”

“Not if you have time to appreciate it,” agrees James (Christopher Timothy).

But happiness is quickly shattered by news of two local boys joining the RAF themselves. “I think it’s their duty,” remarks the boys’ father, but Siegfried is visibly shaken. “The politicians have failed,” he murmurs as the boys go to report. “Now it’s up to people like you… to pick up the pieces.”

“If Wishes Were Horses” aired in January 1980, just weeks after Britain’s steel workers went down for the first time in more than half a century. This strike would last 13 weeks, ending just days before the third season of All creatures great and small did, the wintry discontent of the world once again provided an invigorating contrast to a gentle series. The finale, which bids farewell to these characters for the eight years that elapsed before season four, ends with the image of Siegfried and James also obliging. “Nothing is safe anymore,” Siegfried murmurs towards the end of the episode.

The same could be said of the world that the third season of All creatures great and small premieres as we enter the fourth year of the COVID-19 pandemic, and amid a rising tide of global fascism that is returning to normal with shocking rapidity. The series premiered in September 2020, less than a year after the pandemic began, and while it might be a bit convenient to suggest that James Herriot and his comical entourage pop up in these moments of widespread despair to rouse us to something resembling hope to lead… Well, if the horseshoe fits.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24372584/siegfriedhorses.jpg)

Image: PBS Masterpiece

In Belgium, as we learn, Siegfried was forced to oversee the mass slaughter of horses, considered essentially worthless once they had finished carrying soldiers into battle. Now he’s being told by his former commanding officer to do the same to River, a racehorse who won’t run (“Good for nothing, but dog food,” grumbles a viewer as Siegfried tries to tame the wild thing), Siegfried Go on .

“Surely we don’t have to repeat the mistakes and atrocities of the past!” he pleads with this man he still calls Major. When the older man asks brusquely how often he can be thrown, Siegfried replies with certainty: “As often as necessary.”

Siegfried is referring to his determination to help River, but his determination is more general. When asked to break the horse, he informs the Major that his job is actually to put the animal back together. It’s the same task we all wake up to every day: the need to play as little part as possible in putting back together a world that feels like it’s about to fall apart so quickly the pieces are in your hands could crumble.

“We’ve got to deal with that, Siegfried,” James says to his partner in the original series. “There’s really no other way.”

“You’re right, of course,” Siegfried agrees. “The human animal is the most wonderfully adaptable of all.” It is unclear whether Siegfried believes his own words. He seems close to tears saying that. But “Surviving Siegfried” ends more with catharsis: River lets itself be ridden. The Major’s horse is saved.

In a flashback segment midway through “Surviving Siegfried,” we learn that only one horse has returned from Belgium: the Major’s personal steed. The authors chose to name the horse Orpheus, and their reasoning seems clear. Like Siegfried himself, this creature – so big and yet so small – went to hell. Now it’s his job to emerge again without looking back.

All creatures great and small can be viewed on PBS Masterpiece.

.png?width=1200&height=630&fit=crop&enable=upscale&auto=webp)