Since 2007 when the first part of the sordid was published survival horror series penumbraand especially since 2010, when Amnesia: The Dark Descent reduced First generation YouTube Bringing gamers to tears, independent Swedish studio Frictional Games has created horror games like no other.

Other modern horror games sometimes offer weapons to calm fear, such as Resident Evil Villageor exceedingly despicable monsters, to make fear the obvious answer, as in SurviveBut amnesia prefers to slowly paralyze you before you really feel what’s happening. The forthcoming fourth amnesia Game, Amnesia: The Bunkerretains the snakebite characteristics of the series but aims to dig deeper through its unpredictable, semi-open sandbox world.

The bunkerDue for release on May 23rd, it will amplify its horror by making players feel like “the storyteller living through.” [the events of the game] rather than being the character in a pre-made scenario,” co-founder of Frictional Games Thomas Griffin told me on a video call. It’s more about establishing that malleable gaming experience than announcing itself as the fourth amnesia Play through hidden lore or storylines.

“How can it be such a terrifying, surreal experience when I’m like, ‘Oh, I know this character. Oh yeah! They’re doing that thing again!’” Grip says sardonically.

Like other Frictional titles, The bunker acts as “ego horror [game] where you’re being chased by some creature and you’re trying not to die,” says Grip. But its core counteracts the latter’s narrative focus amnesia Game, rebirthreleased in 2020. “We felt [in] let go rebirth, there was a lot of emphasis on just bringing the story together and we were interested to see, ‘Can we do a shorter, more focused project?'” says Grip. “Then [Bunker creative lead] Frederick [Olsson] came up with the idea, ‘Well, let’s just make it a monster, a weapon, World War I.’”

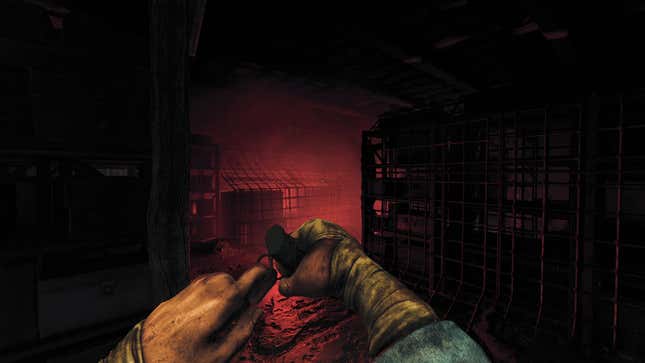

In the game, you are French soldier Henri Clément, trapped in a stuffy WWI bunker with only a revolver, a dying generator, and scattered crafting items to fend off the prowling monster that’s always on the verge of an attack.

Like the first resident Evilsays Grip, where “you’re in the house, then you unlock new areas, but you always go back to the room you started in”, in bunkeryou “start in the bunker, you end in the bunker.”

But even though it’s a compact game, The bunker is made bendable through randomization, affecting aspects of the game like the placement of items and the way you attempt to escape the game’s partially open world. For example, if there’s a locked door, “there are a lot of ways to open that locked door,” says Grip. “We’re not holding your hand. Because of the randomness [even the game’s developers] don’t know the best way to open the door.”

The bunker works with a psychological emphasis that Grip wishes for more horror games.

“Horror, to me, is a safe place to bring up really disturbing things, but it’s kind of okay to digest it as it is [otherwise abnormal].” He brings up the 2005 David Slade film Hard Candy, where a 14-year-old encourages a sex offender to commit suicide. It’s very “hard to watch, but you can do it because it’s a horror movie.”

“I’d rather make horror with a capital ‘H’ than a horror game,” he continues. A horror game is successful when fear is so inseparable from the gameplay, says Grip, that separating them would be as unthinkable as removing all the guns from a shooter.

So horror comes into play The bunker‘s bones, aided by its simple but oppressive surroundings.

This no-frills horror is a different route The bunker Deviates from previous Frictional titles, most notably 2015’s sci-fi survival horror soma, which has such a strange underwater environment, Grip says that “people used all their intelligence” to decipher where they were. It’s a Frictional-favored type of “spookiness where the players do most of the work,” he says, though bunker follows his instinct: “It’s dark. you have to get out These kinds of simple setups are one of the key aspects of [The Bunker’s horror].”

Instinct is partly what compels Grip to horrify in the first place. When I ask, he tells me he’s not necessarily inspired by any particular piece of horror media, but by the “interesting questions” they make him think of.

For Grip, horror offers “ways for us to deal with deeper questions that we have,” such as how ghosts are foggy answers to the mysterious afterlife. Or the way horror makes us consider other uncomfortable but less-anticipated questions like, “What if you were trapped in a room like this?” he says.

“What if that had happened to me?” he begins to wonder inwardly. “What am I doing feel about it?”

He tries to capture how haunting horror can be by not focusing on specific monsters in his games, but evoking feelings, even ones that you can’t quite name. And because of its unpredictable world design The bunker seems to be the best for getting players to consider the most terrifying questions and the equally terrifying feelings that come with them.

“You always have to think twice because you never know which door is going to be booby-trapped, where the monster is going to pop out,” says Grip The bunker. “This is brand new [to Amnesia games],” and be [requirements] are a bit different in terms of testing. Normally we would have a section where we say, ‘This is the second encounter section.’” But because bunker‘s sandbox design, “everything is a potential encounter area.”

That should improve replayability. “There are many ways to do that [navigate the bunker], and the game is also not as long as four to six hours. Hopefully you feel like there are things you could have done, places you could have gone,” says Grip. “I hope that’s the case from a purely commercial point of view, but I think so [replayability] is also very connected to the experience we want to achieve,” he continues. “The players should […] Explore the game organically and don’t be afraid to experiment.”

Grip believes that a good horror game, like a good horror movie, should capture its idiosyncratic, foggy atmosphere. But it also has to have interactivity, something specific to video games, “in a way that feels natural.”

“Say you have a knife and the player has to pick it up and put it somewhere else,” he says. A keen developer should “position the knife in a way that is likely, although not guaranteed, to cause the player to drop it. Then the player drops it, knowing that it was their fault for dropping that object. Then it makes a noise, and [the player hears] a monster and says, ‘Fuck, I screwed up.’”

But it’s inevitable that some gamers will shy away from “taking full advantage of interactivity,” says Grip.

“That’s the craziest thing about horror: you willingly submit to it.” That incomprehensible craving for adrenaline can lead to one of two player reactions, Grip says, either “I’m scared and I’m having a good time” or “I’m scared and this is so frustrating.”

Since players are participants by definition, Grip says horror developers “need to be a little kind to them” by offering more options during gameplay.

“When they’re that scared, they’re not ready to explore everything [in a game], I mean, that’s great. This is natural. But if [that hesitation] is constant for several hours, where players just run off one end or slowly crawl through another, it’s not going to be fun.” Gameplay should accommodate both hesitant and braver players.

But ultimately, players’ personal fear tolerance is as important as a horror developer’s attention. And if a player is really looking to stay petrified, Grip says developers should go for it.

“I’m still very proud to have reviews on the original Dark Descent where the players say, “Five minutes. That’s all I can take I will never play this game again, which means extremely poor user retention rates,” he says. “But for the game we’re making, that’s good PR.”

He doesn’t shy away from other negative emotions either.

He remembers getting feedback from the start soma Tester who says a character’s backstory made the game “meaningless”.

“‘Oh, a negative emotion! How wonderful!’” thought Grip in response. “They’re actually experiencing something, they’re having an emotional response to something fictional.”

With its smooth gaming experience, bunker creates opportunities for a rainbow slick of emotional response. Even more so than in previous Frictional games, where developers “unintentionally reduced gameplay and player freedom,” Grip says.

With The bunkerShe really wants to bring the studio back and dial in [agency] even more so than in the past, with the randomness of the game and so on,” he continues. “My hope is that players will feel that openness” and share a “holistic experience, even if their playthroughs are very different.”

“If that’s the legacy of the game, then I’m really happy,” he says.