The Boy and the Heron is the masterpiece of legendary director Hayao Miyazaki. The 2023 Studio Ghibli film is a triumphant work of art that revisits and questions every theme Miyazaki has explored throughout his long career, in numerous animated films that have become classics around the world. To accompany the film, there is now a documentary called Hayao Miyazaki and the Heronis available to stream on Max and is an impressive feat in itself. While the documentary documents the production of the animated film, it reflects the questioning spirit of the film, examining the past and future of Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki himself.

The Boy and the Heronis, as Hayao Miyazaki explains in the documentary, not a film about his own creative legacy. It is a story about the death of Isao Takahata: one of the founders of Ghibli, director of The last fireflies And The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, and “longtime ally, rival and friend” of Miyazaki. But although Takahata died in 2018, our documentary begins five years earlier, with Miyazaki’s promise that he would retire—this time really—after the publication of As the wind rises.

In retrospect, we know that the director returns from retirement and brings with him the original idea for what later The Boy and the Heron to long-time producer Toshio Suzuki in 2016. But Takahata’s death overwhelms Miyazaki in production, and although the idea was conceived before his death, The Boy and the Heron is ultimately a product of Miyazaki’s mourning of this loss. That is, if we can believe him.

Miyazaki seems quite stunned by the loss of his friend. During Takahata’s memorial service, for example, he tells an anecdote about a moment the two of them spent at a bus stop in the rain. Producer Suzuki, however, admits that he doubts that this moment ever happened, suggesting that Miyazaki is confusing reality with images from his own films, in this case a famous moment from My Neighbor Totoro.

The documentary emphasizes this blending of fact and fiction by repeatedly inserting shots from Studio Ghibli’s collection of iconic works. During Miyazaki’s story about Takahata, for example, the film suddenly jumps to this iconic shot in Stretch. It’s an editing trick used to great effect, as it detaches the audience from reality, just as Miyazaki – and to some extent all artists – constantly shift between the real and imaginary worlds in their minds.

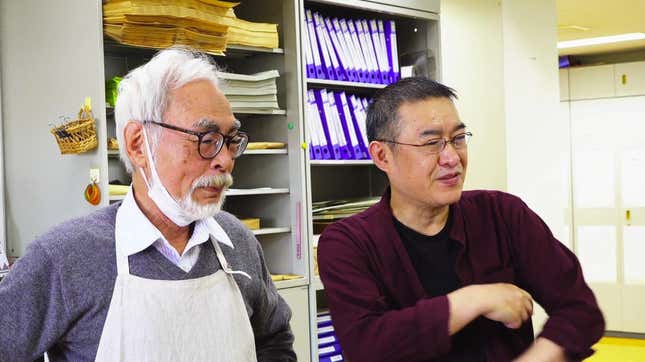

The director deals with his grief in the only way he knows how – through writing. He overcomes the barrier between realities even further by making the people around him, the living and the dead, into characters in The Boy and the Heron. Producer Suzuki, whom Miyazaki describes as an imposter, is the imposter heron, and the documentary alternates between shots of both of them giggling slyly. The late Takahata is the mysterious old great-uncle, and Miyazaki himself is Mahito, the film’s protagonist. Further shots of the real people being confused with the animated counterparts Miyazaki paired them with in his head give us a glimpse into the madness of the method.

Isao Takahata is not the first or last death that Miyazaki has to deal with during filming. The Boy and the Heron. It is a production that is unfortunately filled with the deaths of people close to Miyazaki, and each death hits the director hard and adds new dimensions The Boy and the Herons own themes of grief and acceptance. With each loss Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli endure, he, like Mahito, becomes more and more angry at the world for taking away the people around him. But Takahata’s death haunts Miyazaki the most. He thinks the late director was the only person who ever “got” him as a co-creator, and now that he’s gone, he sees him in everything from a lost eraser to a thunderstorm. The documentary keeps switching back to the late director cycling down a street and turning the corner, just out of reach. And as you watch, you begin to see Miyazaki’s perception of the world – and of The Boy and the Heron– thanks to this incredible documentary work.

But Miyazaki’s story is not the only one that exists. Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron has its own perspective and highlights a filmmaker who seems to be more preoccupied with life than death throughout the filmmaking process. In The kingdom of dreams and madnessIn an earlier Ghibli documentary filmed before Takahata’s death, Miyazaki is more relaxed about the prospect of his death and the fate of Ghibli should he die. At one point, he laughs when asked about the future of the studio and replies that the future is clear. “It’s going to fall apart. I can already see it.” During production of The Boy and the HeronThe director, however, affirms his desire to continue living and creating despite the cloud of death that surrounds him. He is preoccupied with Ghibli’s legacy. Snippets from past films creep into his mind as often as they do in this film, as they represent not only his life’s work, but that of Takahata and countless others. He wants there to be a next generation that can pick up a pencil.

Enter Takeshi Honda, known for his work as a character designer and animation director at Rebuilding Evangelion Films. Released as The Boy and the HeronHonda, the supervising animator on The Movie, belongs to a younger generation, as Miyazaki likes to put it. He is a spry 56, while Miyazaki is 83 (in 2024). His new way of doing things immediately irks the director, despite the newcomer’s obvious skill. As production progresses, however, Miyazaki discovers a new friendly rivalry in the form of Honda’s presence. The collaborative and sometimes combative relationship bears hints of Miyazaki’s dynamic with Takahata. Maybe there are other creators out there who can understand Miyazaki, and – just maybe – Honda is one of them. But the old man has doubts.

Miyazaki has always been a perfectionist. In the past, we’ve seen him tinker with animations for days to get them as perfect as only he can, such as the complicated airplanes he was obsessed with during the production of. As the wind rises. So many shots in Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron show the director throwing away the efforts of others and sometimes his own less successful attempts. Yet one particularly difficult shot, where Mahito strolls down a doorway near the end of the film, sees Miyazaki and Honda face off again. We see the director pick up Honda’s version, as we have many times before, and hold his own to replace it. Yet Miyazaki looks at Honda’s work, in which the younger animator makes Mahito disappear through the camera itself, and he can’t help but recognize the incredible talent on display here. Miyazaki throws his own version in the trash. Honda’s interpretation of the scene remains one of the most subtle and impressive moments in the final version of The Boy and the Heron.

Miyazaki may see himself as Mahito, but in this moment, as in many others, the documentary suggests he is more like the great uncle of animation. He is desperately searching for a sign that the next generation can create something for the future, something new that not only emulates his own work but goes beyond it. This creative drive would be a true fulfillment of the legacy of himself, Takahata and Ghibli. In his relationship with Honda, he seems to find glimmers of it.

The truth behind it The Boy and the Heron lies somewhere between Miyazaki and the perspective of the documentary. He is not just Mahito or great-uncle; he is both at the same time. In fact, he is everyone in The Boy and the Heron in a way. The trickster heron who convinces Mahito to go on this journey is also Miyazaki convincing himself to make another film. Every character from every Ghibli film that was created in Miyazaki’s mind carries a piece of him within them. The director himself says that in order to create these works of art, he has to open his mind to the world. The Boy and the Heron is a masterpiece in which Miyazaki reveals himself to the world in a way he never has before. No wonder the documentary begins with a shot of the director naked in an onsen.

Although Miyazaki is obsessed with the death that is taking place around him and jokes about his own inevitable death, he lives. The end of As the wind riseswhich was once supposed to be the director’s last film, ends with the simple commandment to live. The Boy and the Heron‘s Japanese title, How do you live? responds to this command with a question. Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron answers this question. “If we don’t create, nothing exists,” says the director. So Hayao Miyazaki creates.

The Boy and the Heron And Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron can now be streamed on Max.

.