Collecting creatures has never been so thought-provoking and beautiful.

In the centre of Brighton, where the city meets the sea, in the shadow of the latticework of a burnt-out hotel, there is a traffic junction where someone has pasted a pair of big plastic eyes onto one of the green figures. I don’t know how long these things last, but if you’re here in the next few days, you might still see it. I noticed it because I’m out with my daughter and she notices these things all the time: a green figure staring at us as we wait to cross the road with the rest of the crowd.

Noticing things is in fashion right now. Have you noticed? There are bestselling books that tell you how to notice more effectively. On TikTok, you can scroll and stop to watch videos of rain on city streets, of the seabed stained red by ripples above your head, of momentary shapes forming and disappearing in the clouds lit by the sun. Tagline: The art of noticing. Here you will find beauty and treasure, gifts that can only be obtained if you first learn to see them.

And then there’s Flock, which feels very much in tune with the genre. It’s a game about wildlife, and it’s a game about collecting objects. But it’s also the foundation for everything else, a game about observation. Its world reveals itself to you, but only when you’re ready. Only when you’re in sync, only when you’re tuned in correctly.

First, a little bit of categorization. Well, a little bit of lineage. Flock is the latest game from Hollow Ponds and Richard Hogg. This is the team that made the almost indescribable snake game Hohokum—”snake game” is a terrible name for a game this erratic, energetic, and experimental—and this one has a bit of Hohokum’s sinuous, propulsive movement that sends you hurtling through the air and grass. This is the team that also made I Am Dead, a holistic death-exploration game inspired by a video of a banana in an MRI. In I Am Dead, you explore the world and its story by looking through its bits and pieces. You rummage through everything like you’re in a giant thrift store. Flock has that feel, too.

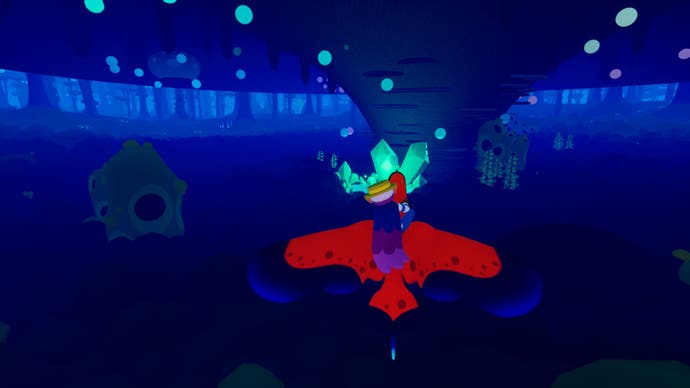

Most importantly, though, The Swarm is The Swarm—and that’s enough. You start at the top of a mountain and explore a landscape of grass, rock, moss, concrete, and wetlands. You ride on the back of a friendly red bird, searching for specimens of the local wildlife. As you find more of these specimens, the world expands, and so do these creatures. How do you hunt them? Hunting, in fact, is precisely the wrong way to look at it. You discover them. You learn to see them. You teach yourself to notice them.

And this plays out in all sorts of ways. When you arrive in a new area, a handful of creatures will be hanging around, flying through the air, sunning themselves on concrete, sniffing through the grass. Everything in Flock is subdued, slightly comical—all in a world where green people wear big glasses—so these flying, sunning, sniffing creatures have candy-colored rainbow stripes, derby cane-like noses, and zippy little wings that hold them aloft. If you discover more, they’ll start to arrange themselves into families: Gleebs, Winnows, my beloved Thrips. But not all are so easy to find.

Some butterflies only appear at certain times of day, rolling gorgeously across the sky during the day, bursting with pinks, purples and golds in a snapshot of the Seventies, while nighttime paints everything a rich blue with a huge pearly moon hanging in the sky. Those thrips glow as they buzz, and usually only appear around the trees when it’s dark. Other creatures need the morning to make their rounds. Others still only bask in the sun at midday.

But timing is only part of the equation. Others require specific environments—trees, long grass, wetlands, a lucky hill. Some hide in leaf litter. Some camouflage themselves as rocks. Some make specific calls.

So from this simple point of view, there are already two ways of looking in Flock. In one of these ways, you’re riding around on your bird, looking for creatures in open areas. But in the second way, you can switch to first-person focus mode, or sit high up, and zoom in on details. This is how you look for things that don’t want to be seen, and have found clever and sometimes complex ways to hide.

You’ll be helped in this quest. You’ll collect a list of all the creatures you’ve found, arranged in neat families, and each missing ecological niche in the list will have a small clue pointing you in its vague direction. Some creatures may prefer a certain part of an ever-expanding biome. Some may require you to track down the males of a species first. Some have fairly sophisticated methods of discovery, while others have only the trickiest, thinnest of crossword puzzle clues. It’ll be enough, though. These hints, combined with an environment that calls out for you to explore, are enough to get you through.

It all works, and feels so unique for a few reasons. First, the movement is so lovely. Flock controls the altitude for you, so you just pick a direction and a speed, and go. The world slides away from you, while certain landscape features propel you high into the air. You’re moving forward, but not just forward. There’s a subtle sense of curvature, like you’re a needle in the grooves of a spinning record. It’s lovely to set off and see where you end up, running through forests, picking up moss, hurtling up Brutalist trees and soft, gentle Ravilious hills and valleys, encountering strange, carved old shattered concrete blocks that hint at an artistic past that can never be recovered.

And then there’s the creature design, which is both hilarious and fantastic. There are treble clefs, air quotes, and carpet runways that flutter in hidden air thermals. They’re absurd fantasies, to which I say: Have you seen a real bird lately? A bumbling patrol admiral, an overfed seagull, a watercolor ghost we call a Jay, dressed in rust and seaside blue and speaking on a dot-matrix printer? The Flock’s bestiary feels like doodles, but it also feels like it was born from studying nature, really observing it, and seeing the wild inventions that make it all work.

(Remember, this is “The Flock,” so you don’t just discover these creatures. Over time, after discovering the right whistle, you can collect them, too, attracting them with a simple mini-game and adding them to the growing herd of animals that follow you. It’s cute stuff.)

Finally, the reason Flock works so well is because there’s a secret ingredient that’s closely related to focus, which lights everything up from within.

That ingredient? When writer Helen Macdonald was young, she was out birding with her father, restless and perhaps a little frustrated by the long wait, when something magical happened.

“Then my father looked at me,” they wrote in the language of H is for Hawk, “half indignant, half in amusement, [he] explained something. He explained patience… He said the most important thing to remember is this: When you want to see something very badly, sometimes you have to be still, stay in the same place, remember how much you want to see it, and be patient.”

Flock does this. And it does it very boldly. Time in video games is compressed: a little time slippage can cause a great loss. Flock absolutely knows this, but it still forces you to stay still, to wait and watch—and it prolongs that waiting and watching beyond what you initially expected. So the other day I spent fifteen minutes under a pink-leaved tree, waiting for something I knew would appear, and when it did, I literally screamed with joy. I spent the entire night—a human, non-Flock night—in the wetlands, looking at promising rocks and not seeing much else. Looking back, I’m not frustrated. It’s not like when I lost a small Lego block as a kid and had to pace back and forth, plowing the carpet with my eyes, a searing pain in my head. Waiting in Flock is beautiful. Patient waiting is beautiful. I’m paying attention. I’m ready for something wonderful to happen. I’m exactly where I’m supposed to be.

Anyway, this is my flock, maybe yours will be different. There’s an entire questline about tracking down stolen items, which involves sending sheep out to eat the grass on certain hills. There’s that creature-grabbing element to the game, and that alone will keep some players hooked. Plus, there’s the fact that Flock is designed to be played online with friends, soaring and gliding above a round globe and observing things together.

But for me, it’s a solo adventure. Give me moonlight, give me my beloved thrips to flutter overhead. Give me that moment, to study biological catalogs, maps, and landscapes so intently that a sausage-like creature with a flared nose appears in the distance and I realize I’ve never seen it before, and my immediate thought is: butterfly. That’s a butterfly. A new butterfly. I’ve been waiting for it, and now it’s here.

Flock review code provided by Annapurna Interactive.