I’m a little worried that Norco won’t be fun. The first comes from indie studio Geography of Robots, a dark game, a story about a region’s bleak, crumbling future. On the face of it, it’s also a serious question, with all its poised point-and-click vistas and dense blocks of prose. Seriously, of course. The seriousness of Norco’s first act is exactly the type of stuff that makes you win you in The New Yorker and Tribeca’s inaugural awards. It’s just that this seriousness sometimes gets caught up in something selfish, a little indifferent. But beyond Norco’s original, slightly bumpy exterior, there’s something strange and adventurous. Grumpy. It’s funny sometimes. A playful spirit bounces back from its sharp political straight edge.

However, this will take some time to draw. Norco starts with you telling your own backstory, or if not telling then digging into it, sorting out dialogue options to fill in the gaps, as you did in Norco’s six-hour narration. A brief, clever little late game mention of one of my off-hand picks in this opening makes me wonder how much of an impact this has – I doubt not too much, and hopefully not too much, if only because I unnaturally Passionate about Hoover recording every drop of the Norco story.

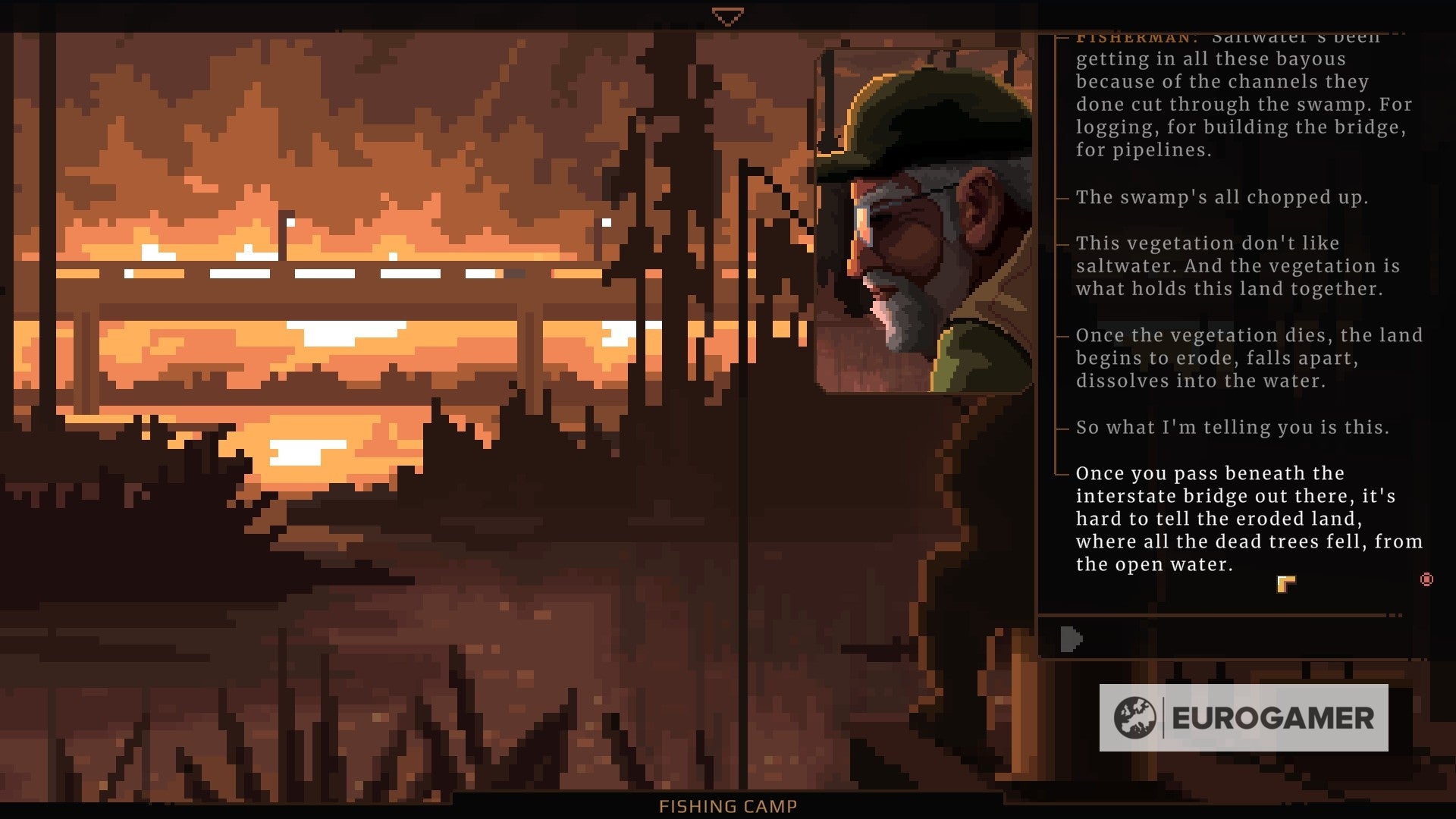

The premise here is a world of industrial, environmental and social decay. Norco, Louisiana is a real place, located in part of the Mississippi River Delta, around a major Shell oil refinery. A non-town named after the New Orleans Oil Refining Company founded here in 1911, the video game Norco is inspired by the real thing (replace “Shell Oil” with “Shield Chemistry”), jumping forward in time by unknown years to the climate crisis It’s starting to pull the world apart. You, a rebellious, faceless teenage girl, return home to learn that your mother, a fickle and dangerously curious former professor, has died of cancer and your troubled brother is missing. What happens next is naturally a mystery, but it’s a very fascinating one, with a drain plug dragging you into the toxic silt of Norco’s toxic community.

Going any further than that would spoil things, but there’s good texture here beyond the plot. Ostensibly clicker, but actually a scatter of mechanics and genres – text adventure, turn-based party battles, ship navigation… poetry…puzzle game? – Designed to fit where it’s needed, the Norco’s advantage is its ability to morph in front of your eyes, dodge you, and slide between your fingers once it’s morphed in your hand. You’ll fight undeserving destitute people, tease dreaming internet boys, dig up conspiracies, chase clues, scribble numbers on paper, tie some loose wire references with clever hints and miss others- On top of that, you’re toiling in the mud as you wrestle with the entire system.

It always carries an authenticity that can only be found when something is made of hard touch points and personal memories.

At times, Norco is a bit covered. When it shifts form, it can often return to the safety of a striking image layered behind flashy, lengthy, poetic prose. That’s always the risk of that dark magical realism-adjacent genre where smart writers occasionally wander too smart in their own good territory. Norco’s genre cousins, though, struggle with the same thing — see: Disco Elysium, Kentucky Route Zero — and it’s mostly just a fleeting moment that these games need to get out of the system. Norco’s more indulgent moments mostly stand out in memory as it sets up an amusing early exchange where an ignorant and snobbish out-of-town director turns to you for help with local phrases to use in his gritty Deep South detective thriller . The game’s mockery of the region’s image in the Hollywood press is justified (e.g., I happily chose “Crawfish Demon” as the killer and “smeared with oyster-flavored peanut butter” as the answer to murder, e.g., the director happily accepted). But then, when you’re traveling through time in a swamp, or reading a crocodile-narrated poem about a “fisherman” who “hooks from a tree with a chicken leg,” it’s nice to have a whole-word bisque.

Still, that’s all textures, and no matter how many odd moments it can get, it’s always delivered with a kind of authenticity that can only be found when something is made of hard touch points and personal memories, about the creation its own home or culture. Its dialogues are rich, earthy and human, its characters are full of fear, frustration, cynicism, hope, their faces rendered in all the extraordinary, gritty details, to that A morbid, rotten Hotline Miami style that apparently sounds through the dial-up modems, whirring generators, horns and horns, and various other electronic or industrial thrums.

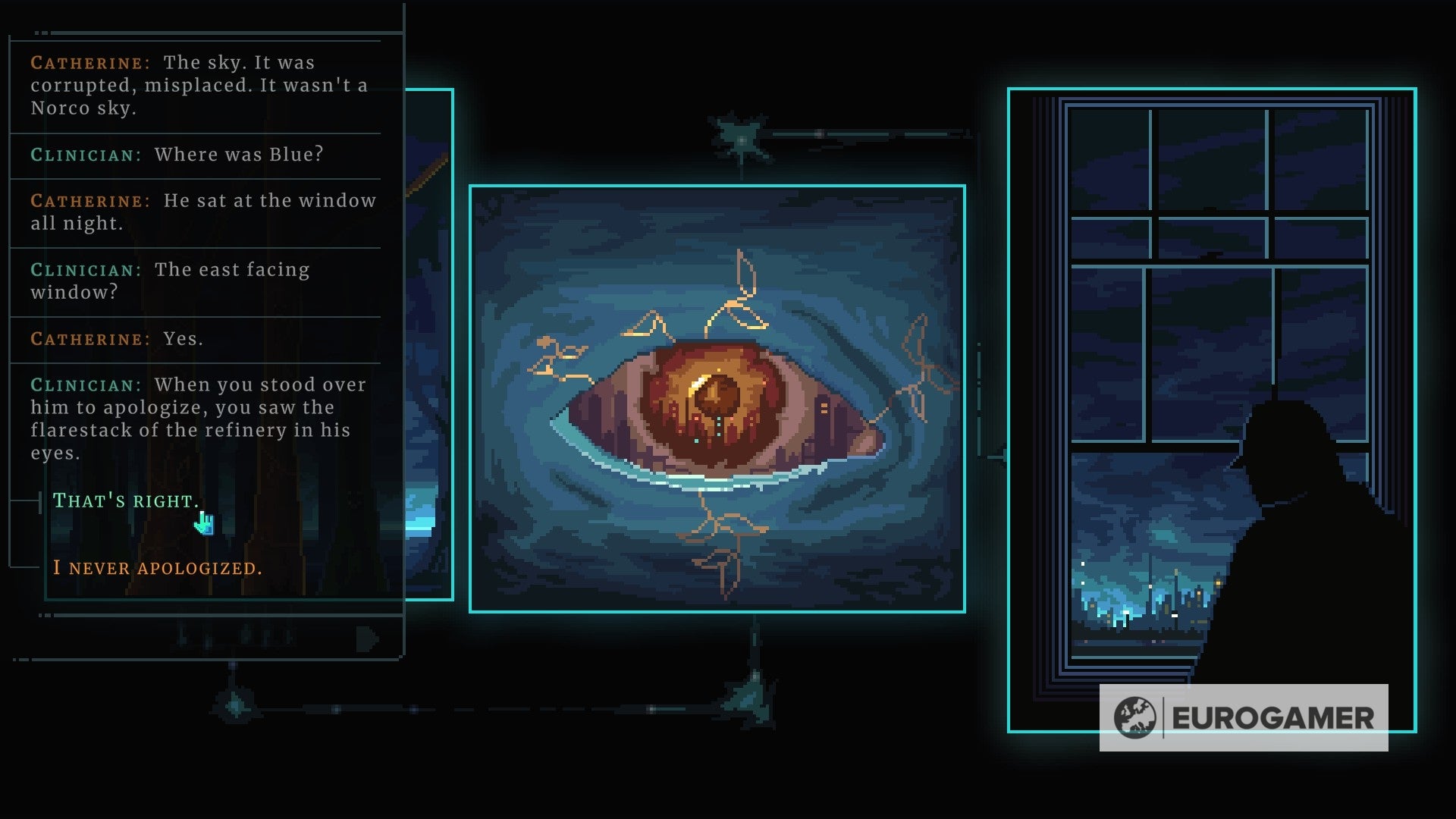

Norco’s metaphorical exuberance is also much more than it misses. The game talks about the stars, the sky, and eyes—many eyes, many eyes—mining the anxiety of watching and watching. It turns the swamp into a brain, explaining the story (and giving me some very thankful reminders) through a kind of mind map that acts as a diary. It mixes neural networks, religions, corporations, and cults with the basic human urge to adapt, feel powerful, or feel alive. It may start with the local dilemma of a global environmental crisis, but will soon expand to artificial intelligence and data, privacy, poverty, disillusionment, the way the modern internet can capture anyone split from an online community, and in a new intensify them in the network. And the desperation and futility of those who see the social divide and want to escape from it and flee.

Playing it is completely and completely engrossing. Part of it might feel like cheating, behind-the-scenes suspense and a trope of story mystery box or whatever else literally on the shelf. But it’s also totally earned. It’s amazing, surprising, and novel. It maintains a dark vigilance for a future on the edge of its blade, contempt for the cynic, and priest-like for the anxious. It is nothing short of extraordinarily beautiful. It’s fascinating like more and more games want to go further and not distract us from these things and go head-to-head with them.