These are my favorite worlds. The best in the world if you ask me. The best of all possible worlds. Not an open world, not free roam, and certainly not an endless or procedural world. Instead, these worlds are a bounded place, a place that is bold and self-contained—compact and weather-tested—like a bird’s nest on a tall branch of an old tree. And it’s also complicated: woven together, each piece is held in place by dozens of other pieces. Maybe picked up, maybe stolen, something that mirrors a thousand other little things that come together.

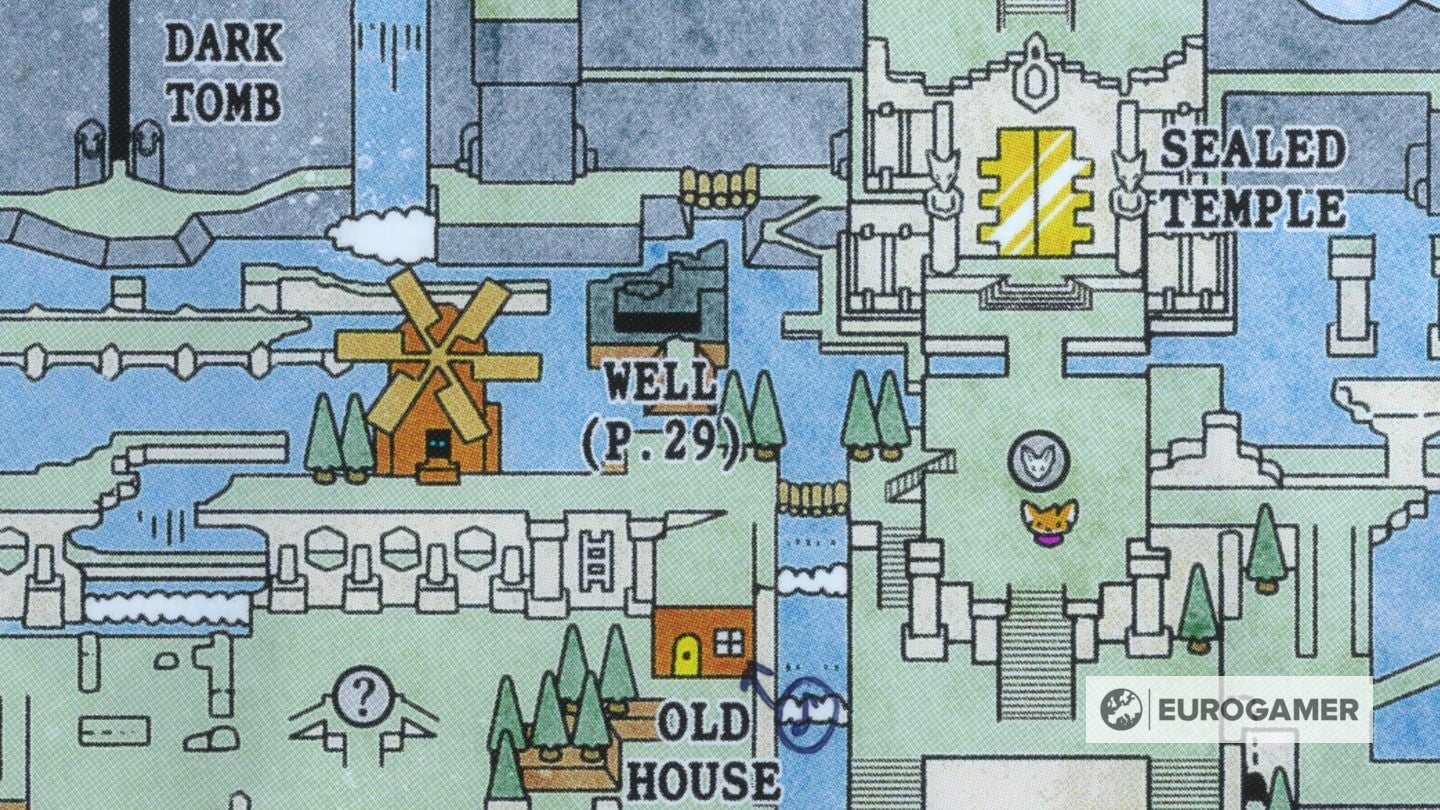

How do birds know when the nest is done? For such a world, a world in a video game, and not on the heights of an old tree, the integrity is in the details. This will be a detail that stays in your head and makes you think: Cor! Look at that. Maybe I should take notes here. a detail. It’s not a big deal. Generally speaking, it’s a small thing. hidden stuff. Hide, say, under a bridge?

Yes! Under the bridge, bonfire. Just say those words and I’ll be back. Late in A Link to the Past, which is still arguably the best Zelda game, and certainly the most faithful to its Zeldaishness, I realized there was a gap in the map: a bridge, and there might be something under it . I finally found a way and there was a sleeping guy lying by a campfire under the bridge. Rustic family life. Get comfortable in an increasingly scary world.

This guy gave me a bottle, an extra one always works in a Zelda game. But more importantly, he gave me something more in that secret fragment of this map that I had to imagine in the first place that might exist in order to actually locate it. He gave me a glimpse into the minds of designers – and of course, how their minds work when they come together. And an invitation, maybe – to encourage my mind to work in the same way.

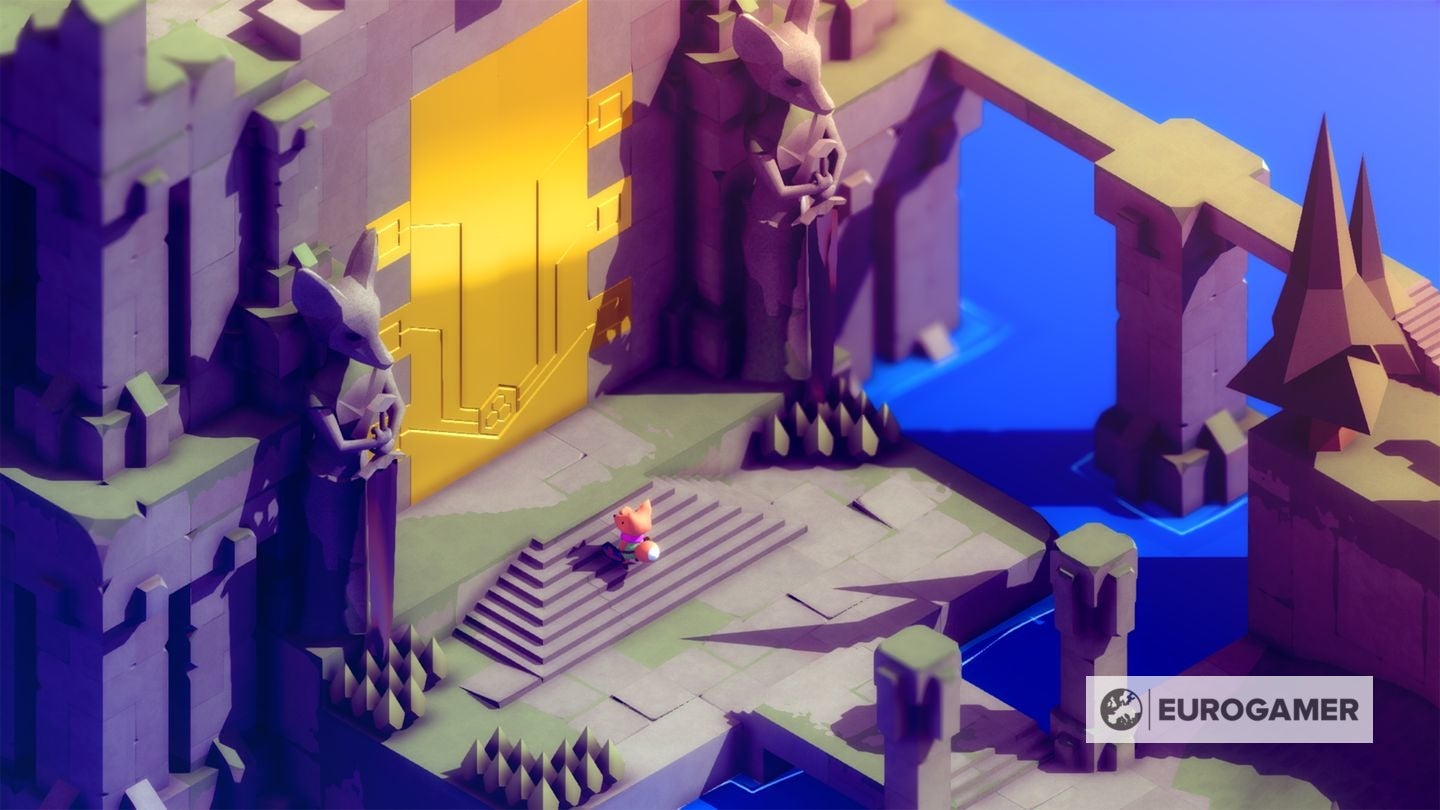

A Link to the Past is just one of the few games that Tunic reminds me of. Honestly, I almost made it secondary: that top-down world of pruning, where Hyrule’s cinnamon roll tree was replaced by a fat little dart, and the boyish hero in green was replaced by a brave fox. But this is not a clone, duplication or silly repetition of precious memories. is the correct synthesis.

Tunic took lessons from A Link to the Past – about how to build a world and layer its puzzles until they become a layer of secrets and possibilities.Like lessons learned from Souls games, in Soulsy fights, you learn by shaking your shield arm when you block, then timing in Soulsy fights, and when you kick off ladders, flashing Glowing Moments of Recognition Lessons learned are on the wall and realizing the long journey through unknown lands has brought you back here

Zelda and Souls come together – not just images or main beats. Instead, Tunic gained understanding by playing with both and really thinking about why they are the way they are – how they create their special effects, in the words of a magician. The Legend of Zelda and Souls and a handful of other games – naming them would be a spoiler – are used almost as writing prompts, as creative pushes into new territory. It’s a borrowed game, but it redesigns what it borrows. Here’s Conan Doyle filtered through Alan Ruskin: Inspiration Internalized and Transformed. Alchemy I guess.

Oh, in other words: Zelda’s success means it’s codified. You will approach each new game and ask: what is the world this time? When can I get the boomerang? Breath of the Wild is a response to this question. In fact, maybe Dark Souls is a response to that in some way. This game is another response.

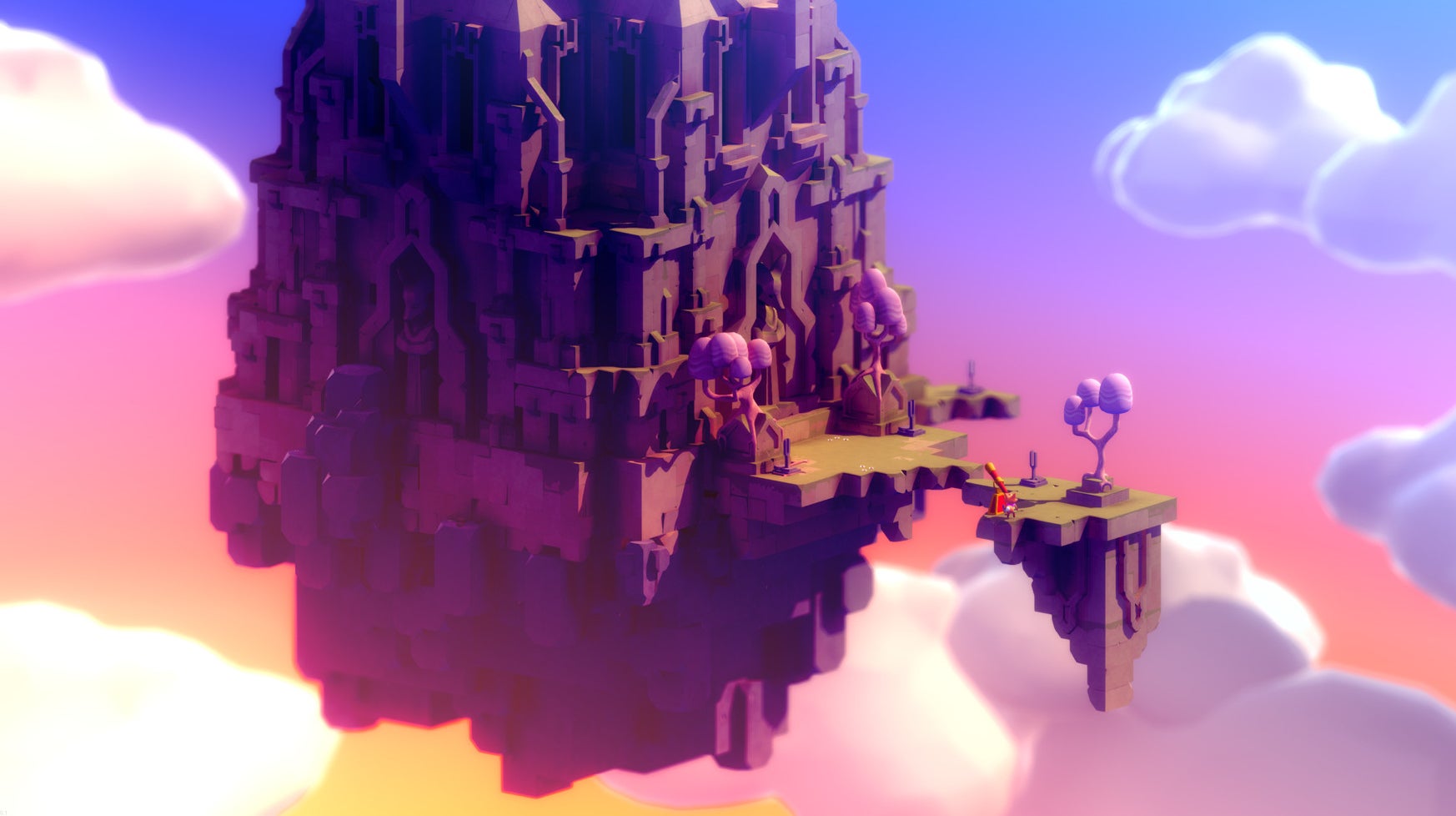

Tunic! So you’re a fox freeing yourself in a bright, clean world. Rock, grass and earth! You explore dappled forests and barren coasts, collecting swords and shields. You deal with monsters, travel through the ruins, and slowly begin to solve an ancient mystery, one boss at a time.

At this level, I think, Tunic is already a very good time. The world has gone from spring fields to crumbling towns—with windmills, of course, and telescopes—to cisterns and temples full of green water, with metal and alien stuff gleaming on the walls. You see the world from an angle that the designers of this place aren’t very good at using to create blind spots where they might put something exciting — a chest, or better yet, a hidden tunnel. They are teaching you to explore the world through your imagination and what is immediately obvious. (At one point, to make the point more clear, they simply turned off the lights.)

Enemies are great. Slime and prickly stuff made of shimmering icy death shards. Skudding’s laser-equipped drone is made of old rock. Similar to the hippo with sword and shield and avant-garde cape to complete the look. One level was full of frogs, and they all attended a kind of frog academy. If you just rush in, each enemy can kill you on their own. Instead, use a trigger target, but don’t rely on it too much – be careful of the many ways it ties you to an enemy when you’re constantly surrounded. Extend your shield, but don’t let it slow you down. Dodge the roll, but don’t let it eat up all your stamina. Use magic items, but don’t forget the mana here doesn’t regenerate on its own.

endurance and Mana? Even here, Tunic makes the most of Souls and Zelda. You can expand your health bar by finding and cashing out certain items – you can expand all your stats this way – but for health you can also collect more estus-flask-equivalents, which are initially distributed For several parts that must be put together, like the Heart of Zelda. Reworked the system for both games, finding the secret harmony until you can’t see the connection.

The same goes for bosses – are they Zelda bosses or soul bosses? Sometimes they’re both, and eventually I’m starting to understand that they’re neither – they’re coat bosses, scary, tactical, light-hearted puzzles that encourage you to respect your character on the fly, pick and choose what you might collect Items like bombs, via new weapons like magic wands or… well, I don’t think I should be spoiling here anymore. Not even the mid-game treat that turns you into a hybrid of Batman and Mr. Tickle.

It’s a good game – explore, defeat bad guys and bosses, level up, open up the world a little and try out new dungeons, work your way, tell yourself, go to the final boss, the moment the world is in balance and all that jazz .but this is also half game. It’s half of Tunic. Maybe less than half, in terms of the time you spend thinking about it, turning it over. “There’s another world,” as the quote puts it — it’s maddening to try to track down who said it in the first place — “but it’s in this world.”

To access the other half – another game nested within Tunic, if you will – you have to step back a bit. Away from foxes, sword and shield, enemies and head-to-head adventures. Consider the entire world, with its jagged edges, distant points that may have unusual resemblances. Think about the things you pass along on your journey that you don’t yet understand. what might they mean? What can they do?

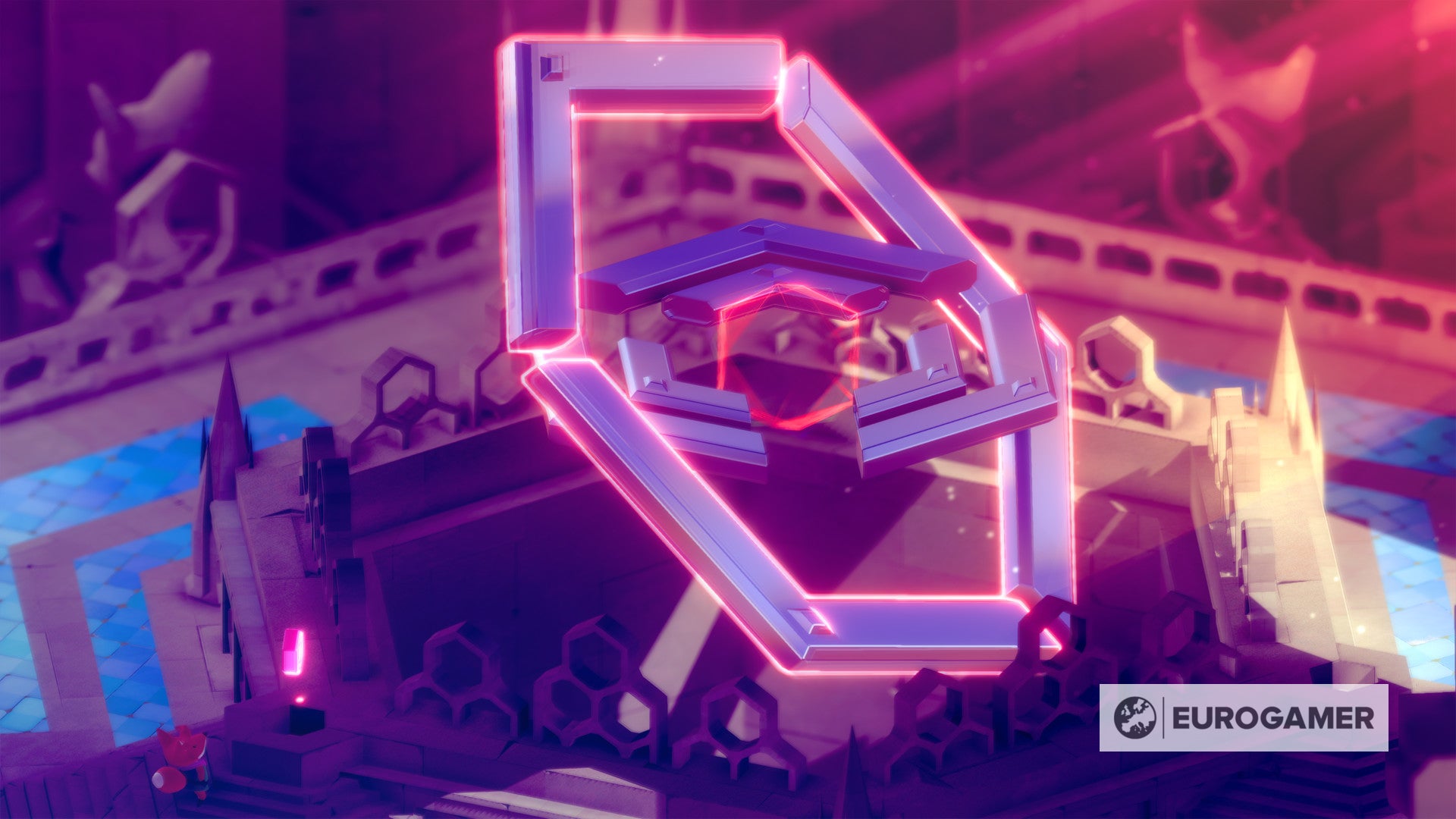

Two things help Tunic’s wonderful hidden game really come to life, one of which I really don’t want to spoil for you, because when I first got it right, I realized that Tunic showed me something I really never saw What the past games do. But does the other thing help? Tunic’s deeper, spooky, menacing, confusing permafrost, works just fine because at first the layers obey the rules of more exposed layers.They need the same idea – just expandedso that you might feel like you’ve gone too far.

That is: in a Zelda game—in a Souls game—you’re used to getting items that allow you to see new possibilities in the landscape and new possibilities in your location. You’re used to encountering features that don’t seem to make much sense for the time being because you currently lack the right lens to view them. So the expanse of Tunic, its beautiful quirkiness, is harmonious because the way you think about it is ultimately the same way you sort out how things work here – understanding items took me an age – and how leveling works, and how travel How fast, and, and…

In bad or even middling Zelda, you get craft and nothing else. At best, you get the imagination, you get dazzled, and you get transported to a new place.

How deep do you want to go? In fact, Tunic’s landscape itself embodies the precision and artificiality of the design: all these clean lines and echoing, repeating angles form a world that adds up on graph paper and a freshly sharpened pencil like a hymn. I’d love to say that you can enjoy the more immediate aspects of Tunic without thinking too much about these things. But really? Tunic’s best puzzles are designed for collaboration and forums and for sharing notebooks and screenshots, yes, but they’re also designed to sit in your unconscious, quietly jot down yourself, and then one day you’ll find yourself While staring at some weird screen, you suddenly realize you know exactly what you have to do with it.

Overall, it kind of reminds me of how I sometimes feel when I’m on vacation, with jet lag in a once-distant country, and I’m going to the supermarket to buy paracetamol or something. I don’t speak language. I don’t understand many customs. Still, many products look semi-familiar. Semi-familiarity is enough to suggest their own potential uses while, crucially, allowing for surprises. It’s exciting, it’s alluring. supermarket! Everything looks great. And quietly unusual. Is that fruit or some kind of loofah? Should I chew these or swallow them for hiccups? Where should I push my cart next?

I think the success of a game like Tunic, especially one that follows in the footsteps of games like Zelda and Dark Souls – depends on getting what I’m going to simply call Distant Supermarket Thinking fun to deploy properly. In the best of these games, full of action, adventure, and wholesome excitement, we’re always open-eyed and always wary of the joys we know we can’t predict. An old idea conveyed in an unfamiliar way; something that appears familiar but is not what it first appears. In bad or even middling Zelda, you get craft and nothing else. At best, you get the imagination, you get dazzled, and you get transported to a new place, in the midst of all this stuff that feels so intimate and stale.

The difference can come down to many things: time, enthusiasm, a clear vision of what you want to achieve, even if it’s very complex and ambitious. There’s more: a certain sympathy for form. Here’s another twisted quote in this regard: They say that only bad poets hate rules. This is because a good poet thrives on constraints, and established expectations can be twisted, subverted, and reversed. They find constraints and traditions driving and accelerating. This is the heart of the tunic.

Consider the fox. I guess you are not an accidental fox in this game. Back at the beginning, my first thought about Tunic was that your fox hero doesn’t actually look like a fox. Bounce too much. Too much cheer. too naive. They don’t match the gorgeous midnight creatures I sometimes glimpse under a bunch of safety lights at the end of the driveway at rare times. Grimace, fiery eyes, one foot raised and stopped halfway. These are cunning animals. It’s projection, I know, but foxes always feel like thoughtful people who know wild and complex ideas. They don’t always bounce around the world happily.

Then, over time, I got it. Your hero in Tunic isn’t yet a fox. They are a cub. So you, the player, must be their fox.