RPGs are a genre where side hustles always threaten to take center stage. Many classic samples are built around a more conscious confrontation between primary and secondary content, more so than you’ll find in today’s open-world games, where everything can be consumed at any time. Think about how Tetra Master in Final Fantasy VIII lets you put the plot on hold for days, or the more dangerous Sokoban-style puzzles in older Wild Arms games. It is in spaces like this that RPG designers sometimes hide their best, or at least their weirdest, ideas away from the pressures and constraints of central production.

First released in 1994 and remastered using the same sprites-meets-polygons visual style as Octopath Traveller, Live A Live is essentially Sidequest: The Game – before I compare it to the level selection cheat in Sonic, I might Should be aware of this. This is a series of loosely intertwined 1- to 3-hour stories set in different historical and/or fantasy periods, each with a colorful interpretation of the colors of the old Squaresoft role-playing games. Like side quests in a traditional single-narrative RPG, some chapters are more successful than others, but all are engaging experiments, and while it’s slightly thwarted by the stop-start anthology structure, the overall grid-based combat system is worth 20 It will take you to the end credits in a few hours or so.

The game’s nine chapters (seven at the start) share a leveling and equipment system, but beyond that, each has a different protagonist – usually a man, it must be said, with a woman mostly in the midst of a difficult situation The maiden- and party members, an iconic mechanic or two and a savory writing style. On the one hand, you have distant prehistory, in which a furry Flintstoner and his ape friend stumble upon a runaway girl while throwing poop at a mammoth. This chapter is a salacious comedy written with grunts, gestures, and speech bubble emojis. On the other hand, you have a Wild West chapter starring a guy with no name — well, a guy with a customizable name — who joins forces with his nemesis to defend the frontier town from outlaws. The episode is feature length with a chewy salon bar script built around a single puzzle: arm townspeople with traps and knock down as many outlaws as possible before the final battle.

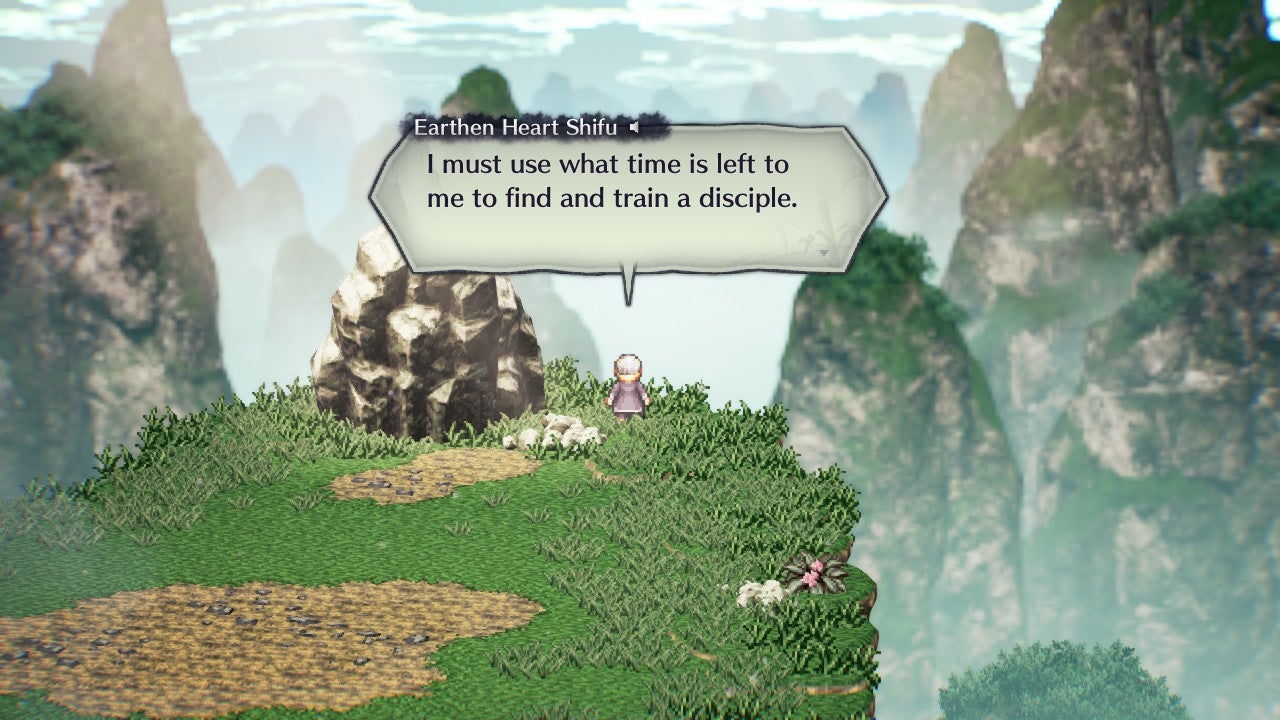

The cheeky advantage of Live A Live’s anthology format is that components don’t have to be universally excellent. The appeal of the game is half pure novelty value and half watching the development team struggle to make the same work fit into different narrative settings. For example, I’m not a big fan of the Empire of China chapter, in which an older martial arts master puts three disciples through training to fight before a showdown with a local gangster. You’re invited to play your favorite game, but don’t have enough time for these mentoring relationships to blossom.

Likewise, I’m not that hard on the far-future level, where you play as a sentient robot on a starship transporting alien monsters. Here, the only fight takes place in another video game in the ship’s recreation room. You’ll spend most of your time running back and forth between elevators in pursuit of a hot-blooded interstellar soap opera, or a few hide-and-seek sessions. But I find myself cheering for the developers anyway, because after all, who wouldn’t want to see the creators of Dragon Quest give it a try in an Alien or Kung Fu epic? Anyway, if you lose interest, you can always switch between chapters using a single save file, and the challenges are balanced so you can solve them in any order.

Some chapters feel more like jokes. The current (aka early ’90s) part is a stripped-down spoof of Street Fighter, starring a party member in many turn-based RPGs who can only learn abilities by copying enemies. As a potential global champion, you pick opponents from a coin-operated arcade menu, then dodge around to lure their funniest moves before a KO. It’s delightfully stupid, though not as stupid as the recent installments, and takes a deep breath, starring a telepathic orphan criminal who joins forces with a punk biker, a Dr. Brown-esque scientist, and a turtle-powered robot Collaboration stops a tech company from turning souls into fuel. It starts with you selling takoyaki and stealing clothes in the park, and ends with a mech punching gizzards out of a giant bird. With several toilet-based puzzles plus a cheerful urban world, you gain the ability to make targets confuse you with their own mother.

Part of what I love about this chapter is that I don’t know what’s going to happen next. But my favorite so far is the Japanese part of the Edo period, where the quiet genius is that it pits you against the game’s own leveling system. You play as a ninja invading a fort to rescue a prisoner and murder a lord dabbled in the dark arts. You’re told to keep the corpse count low, you’ll miss out on certain rewards if you build a streak, but you’ll be wiped out in impossible fights if you run past or flee every encounter. Fortunately, you can murder non-human beings, such as ghosts, with impunity.

This proves the basis for expanding social stealth puzzles, such as the killer mission set in Sekiro’s Ashina Castle, where you track down enemies you’re allowed to kill while feeling a clockwork game full of revolving doors, secret rooms The act of space is accessed using your ears and some creepy moments involving puppets and shadows. The current and future chapters are one-offs, and the Edo part needs to be replayed, which is the part I would most like to see Live A Live develop into an indie game.

The main downside to the Live A Live anthology structure is that the battles don’t fully evolve within the first 15 hours, as each initially unlocked time slot needs to be accessible enough to be the player’s first choice, with its own challenges and micro-complexities arc. Luckily, the last two chapters were a hit, and the last episode in particular was a chance to really get the combat system on track – recruiting former protagonists from around the map, venturing into character-themed puzzle-solving dungeons to Get their ultimate weapon.

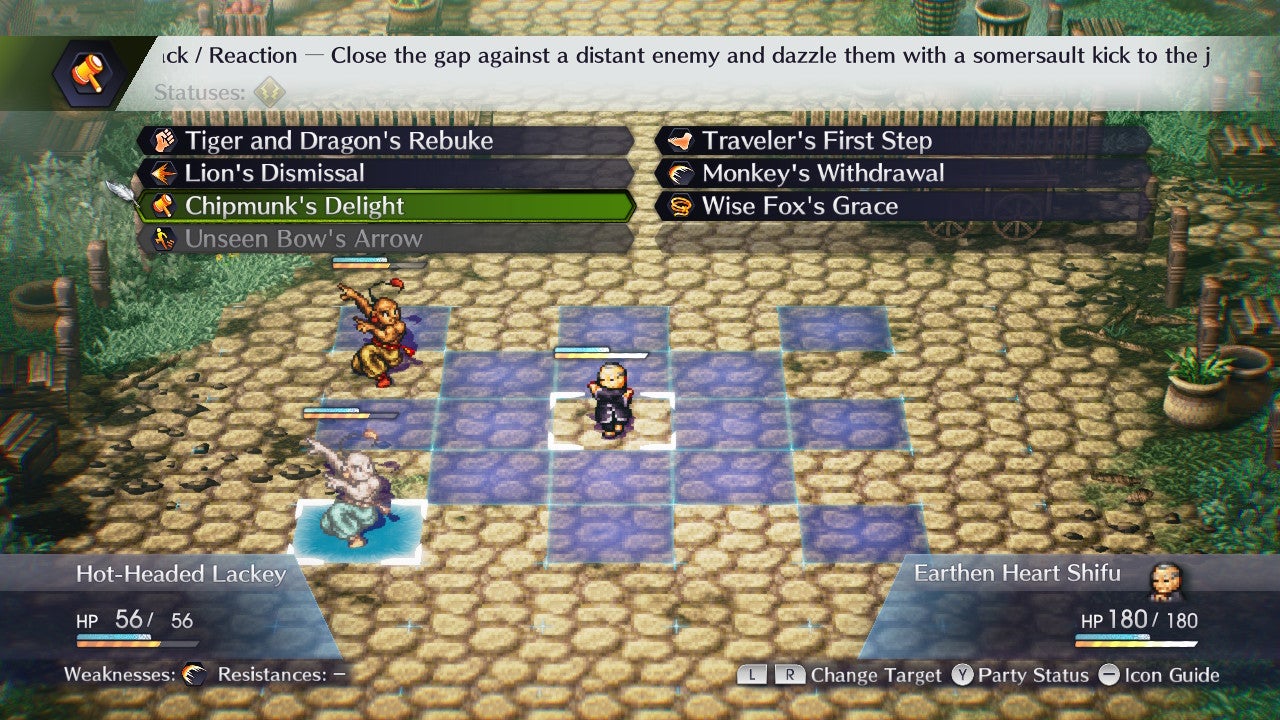

So, fight! I should probably instead tell you how it works, no? Bread and Butter: Characters have action bars that fill up when another character moves or acts. Battles unfold on a narrow square grid, with some beautifully drawn bosses taking up a third of the game space, and you can move freely during your character’s turn until interrupted by enemy action. Attacks and abilities affect different tile patterns: melee moves will of course target adjacent tiles, while more advanced spells may strike diagonally. Some abilities affect terrain, filling blocks with water or fire. Others have a cast time during which enemies may slide away or attack, knocking your character out of position.

There are slightly more types of status effects, from poison and paralysis to debuffs that lock in certain abilities. Enemies may also be resistant or vulnerable to certain attack types, although this is not as impactful as the shocking enemies in Octopath Traveller. While equipment selection can be decisive, you don’t have to do much poking around in the menus between scraps: characters are fully healed between battles, while upgrades stat boosts and unlocks are selected for you. There are some areas that are randomly battled, but most enemies are visible on the world map and can be easily overtaken (the ninja can also disguise himself in the background and have guards wandering around him).

Live A Live is both the perfect project and one of the original sources of Square Enix’s current aspirational approach to retro RPG development…these games are not just a tribute to some modern features, but an alternative retro future that feels quaint and sleek once

The combat system is weakest when viewed as simple, your stats vs. mine events, and strongest when viewed as chess’s quirky cousin. It all depends on how these AOE abilities determine your understanding of the board, and thus your opponent’s characters. The recent offender is a glorified car that fires psychic shockwaves horizontally and vertically, for example, making him less effective against enemies that move like a bishop. shinobi gets some powerful AOE moves that leave terrain effects, but those moves also cover the tiles under his feet, so you have to keep dancing with him.

The Kung Fu master lacks ranged attacks: he’s just closing in, then using skills to move himself or his target to a square – much like a martial arts legend denying his opponent an opening. The Cowboy, by contrast, is all about range and single-tile attacks: Part of what weakens the Raider’s ranks in the Wild West section is his weaker ability in crowds. The game’s most satisfying combat expands these underlying issues into full-blown spatial puzzles: among them there are fragments of enemy bosses that can be killed to defeat everyone else. You’ll want to open your way to these VIPs by using knockback skills and smashing formations through doors, rather than systematically clearing out regular employees.

Live A Live is a long-running whimsical game with far more farting jokes than loud philosophical takeaways. But behind it all, there’s a touching, mildly radical morale of connecting people in different times and places. Without revealing too much, the final revelation is that every chapter is in some way the same struggle, evil doesn’t seem like the ultimate antagonist, but a toxic meme outside of a linear chronology that has to be done once defeated again.

In this regard, Live A Live is both the perfect project and one of the original sources of Square Enix’s current aspirational approach to retro RPG development, which is not simply restoring old games but dividing reality into a meta-historical dimension, SNES The brand’s pixel sprites coexist with sparkling 3D lighting effects and cinematic transitions. As I wrote about Octopath Traveller, these games aren’t just a homage to some modern features, but an alternative to retro-future that’s both quaint and sleek. They fuse what was past and present into what is possible, fostering a speculative, open-ended view of gaming history that contrasts with the exhausting industry rhetoric of hardware generations and “cutting edge” technology about to be dulled. contradict. You might conclude that this is a historical vision that is entirely on the sidelines.